Bigelow addresses PFAS contamination in Casco Bay and beyond

Dr. Christoph Aeppli. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Dr. Christoph Aeppli. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

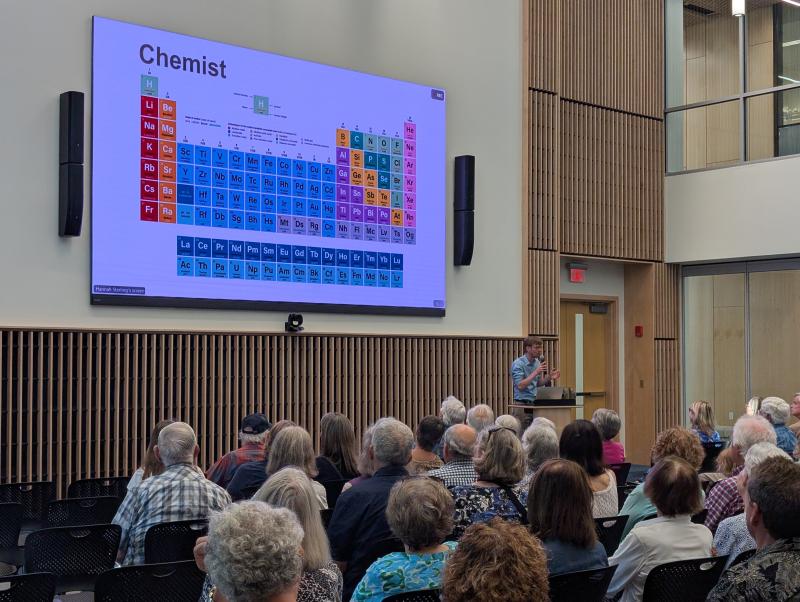

Bigelow presents “PFAS in Casco Bay: Tracking the Fate of Forever Chemicals on Maine’s Coast." CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Bigelow presents “PFAS in Casco Bay: Tracking the Fate of Forever Chemicals on Maine’s Coast." CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Hannah Sterling presents an interactive map of PFAS concentrations in Maine. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Hannah Sterling presents an interactive map of PFAS concentrations in Maine. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Hannah Sterling. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Hannah Sterling. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Dr. Christoph Aeppli. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Dr. Christoph Aeppli. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

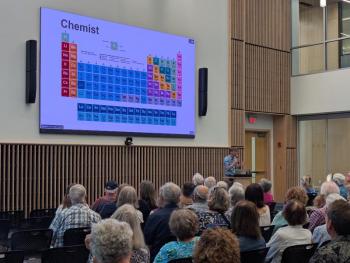

Bigelow presents “PFAS in Casco Bay: Tracking the Fate of Forever Chemicals on Maine’s Coast." CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Bigelow presents “PFAS in Casco Bay: Tracking the Fate of Forever Chemicals on Maine’s Coast." CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Hannah Sterling presents an interactive map of PFAS concentrations in Maine. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Hannah Sterling presents an interactive map of PFAS concentrations in Maine. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Hannah Sterling. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Hannah Sterling. CANDI JONETH/Boothbay Register

Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences (BLOS) held “PFAS in Casco Bay: Tracking the Fate of Forever Chemicals on Maine’s Coast” with a crowd of about 165 in-person and online attendees. The talk was the third of this season’s Café Sci presentations, sponsored by HM Payson, focusing on human and marine health concerns in Maine. BLOS president, CEO and senior research scientist Deborah Bronk introduced Dr. Christoph Aeppli, a senior research scientist, with a background in environmental chemistry and a specialized sabbatical in PFAS, and Hannah Sterling, a research associate holding degrees in marine biology and chemistry, who also participated in a National Science Foundation-funded Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) program.

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), often called "forever chemicals,” are human-made compounds found in numerous consumer products due to their useful properties like non-stick and water-repellent qualities. Aeppli walked the audience through the chemical basics of the group of compounds referred to as PFAS, which includes more than 4,000 different industrially produced compounds, not all of which are bad, but many have lasting environmental and documented health effects in humans and wildlife.

Aeppli shared a report from the National Academies of Sciences that identified increased blood pressure and cholesterol levels, decreased immune response to viruses and vaccines, increased risk of some cancers and increased risk of thyroid disease as the primary health concerns associated with PFAS exposure. Further, PFAS enter the environment through industrial discharge, landfills and wastewater, leading to human exposure via contaminated drinking water and food. As much as 10-40% of PFAS accumulation in humans can come from drinking water (depending on where you live) and another 40-80% can come from food. “It highly depends on where exactly you live. Our drinking water is where we get it. Another 40 to roughly 80% of PFAS come through food, and this is because once it's in an environment, it tends to accumulate in something like fish, it can accumulate in plants. It loves going into leafy greens, and the grass cows can eat, so therefore it can accumulate in meat. And it can then even go into their milk,” he said.

Aeppli discussed traditional remediation techniques as well as emerging technologies for treating the pollutant. According to a Center for Disease Control report Aeppli shared, between 1999 and 2020, Americans saw an 80% reduction in the amount of PFOS (a PFAS compound) in our blood. This reduction is attributed to steep declines in PFAS production in the early 2000s in the U.S., Japan and Western Europe. However, products containing PFAS compounds have risen in countries like Poland, China, Russia and India.

While Aeppli lectured on the effects of PFAS in America and around the world, Sterling made the second half of the talk more local, focusing on Maine's significant challenges with PFAS contamination, which became widespread through the historical practice of spreading wastewater treatment plant sludge on agricultural lands. Other sources of PFAS contamination listed were paper mills, landfills and wastewater treatment plants. She spoke of state-level testing efforts in soil, freshwater fish, and deer, even leading to "do not eat" advisories in some areas such as Fairfield. Her work details oceanographic research conducted in Casco Bay, highlighting the transport of PFAS from inland sources via rivers and identifying firefighting foam spills as a major, acute contributor to coastal contamination, specifically the 2024 spill at the former Naval Air Station Brunswick (NASB); the spill released 1,450 gallons of PFAS-laden foam into Harpswell Cove.

Future research aims to further investigate PFAS in marine sediments and organisms. Sterling has been collecting and analyzing core sediments from Casco Bay. She spoke of her relationship with Maine’s coastal ecosystems from the time of her youth through today and takes pride in Maine’s proactive stance in searching for PFAS and conducting statewide tests, distinguishing Maine from other states.

Aug. 6, BLOS will host the final Café Sci talk for the season, "Ocean Epidemiology: Tracking Marine Diseases to Protect Fisheries and Ocean Health." Preregistration is required. Since the BLOS open house July 11, the laboratory has received many requests for tours of the new Harold Alfond Center for Ocean Education and Innovation and will host hour-long tours each Friday in August from 11:30 to 12:30, according to a post on X. Registration is recommended.