Maine lobstermen: The other endangered species?

When President Biden signs the $1.7 trillion omnibus bill into law, Maine’s lobster industry will take a six-year step back from the brink thanks to the efforts of Maine’s congressional delegation which secured a last-minute addition that put further restrictions to protect endangered right whales on hold.

But Boothbay area lobstermen caution this does not end their concerns.

“The pause doesn’t mean this is over,” said Boothbay’s Troy Plummer, member of Maine Lobstermen’s Association (MLA) board of directors and lobster boat operator for nine years.

“Everything is status quo until 2028, but we’ll have to do our homework,” said Boothbay Harbor’s Clive Farrin, lobsterman for more than 20 years and past president of Downeast Lobstermen’s Association. Farrin offers three lobster tours a day in summer aboard his boat, Sea Swallow.

Nick Page, lobsterman and co-owner of Atlantic Edge Lobster with wife Kristin and brother Andy, said it has been a difficult year. “It’s not a real profitable year, fuel prices are high, bait prices are high and it brings a lot of stress.”

The Boothbay region lobster fleet numbers around 100 boats, according to best estimates from several members. It contributes about two million pounds of lobster a year which accounts for about $8 million per year in lobster from our peninsula alone, according to Plummer. The Maine Department of Marine Resources website shows statewide lobster landings of $730 million in 2021.

In Maine, lobster licenses, held by the individual, cannot be sold or traded. DMR says there are about 4,100 active commercial harvesters in the state. There are 160 license holders in the Boothbay area, according to Plummer. As he explained, Zone E, which includes the Boothbay region, Bristol, Georgetown, Small Point, Wiscasset and Westport Island accounts for about six million pounds of lobster each year.

Nick Morley, lobsterman and co-owner of a bait operation with Andrew Hallinan, points out there are also sternmen, dock workers, bait dock workers, “...probably upwards of another 200 people for all the buying stations in Boothbay, Boothbay Harbor and Southport.” Farrin estimates the lobster industry in Maine supports 25,000 shoreside jobs statewide. In addition, the Maine Lobstermen’s Association website lists 38 categories identified as “Businesses that have a connection with lobstermen and the Maine coast,” among them accountants and car dealerships.

Impact on region’s economy

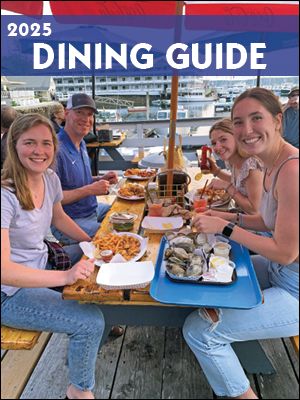

At times romanticized due to its beautiful coastal setting, lobstering is a powerful economic driver of the Boothbay peninsula so dependent on tourism. As lobster goes, many believe, so goes the area’s economy.

“It’s the ripple effect,” Farrin explained. “Commercial fishing impacts the Maine economy by $750 million annually and lobstering is the lion’s share of the fishing business.”

“There are many more offshoots that are all affected by this very materially,” said Jon Nicholson, chief lending officer of First National Bank in a recent phone interview. “It extends far beyond the water to other businesses that deal with the lobster industry.”

He identified it as ranking fifth of the bank’s top 10 industry concentrations for lending. “Without this pause there would be larger ramifications beyond the lobstermen,” Nicholson said. “Folks hesitate to invest, new trap orders have been cancelled and boat sales have slowed.”

To show its commitment, the bank recently donated $300,000 to MLA.

“Our harbor would empty immediately,” said Carousel Marina owner Jax van der Veen when asked what the impact would be if the fishery closed. “Every storefront and business would be affected – lobster dinners are half of our seafood sales,” she said.

“It’s the fabric of our community,” Brady’s owner Jen Mitchell said. “I wouldn’t have people here if we didn’t have lobster.”

Ralph Smith, who owns Mine Oyster and Boat House Bistro restaurants as well as Hawke Rentals, agreed. “Half of the year we’re a tourism community and they’re here for the lobsters. We offer it about 20 different ways in the two venues. It’s about 25% of the business in the summer.”

At Atlantic Edge, Kristin Page explained, “Most of our business is wholesale to local restaurants.”

How did we get here?

Since 1872, regulations have been in place for when and how lobster is caught. In recent years, NOAA imposed tighter restrictions to protect right whales from rope entanglements which it says are causing the species to decline.

The lobster fishery in Maine complied with previous NOAA rules but pushed back against the most recent NOAA requirements, among these use of equipment which is not readily available, saying the two-year deadline for compliance would end commercial lobster fishing in Maine.

MLA brought a suit against the NOAA restrictions which is now with the appellate court. Not content to wait, Maine’s congressional delegation and state officials worked to craft the six-year pause added to the omnibus bill. It provides for funding “to support the adoption of innovative fishing gear deployment and fishing techniques to reduce entanglement risk to North Atlantic right whales...”

Where are the whales?

Is looking for a right whale in the Gulf of Maine like looking for a robin here in February?

“A lot has happened in the last decade – increased mortality, decreased reproduction, and they’re having to change when and where they’re feeding due to climate change,” Philip Hamilton, a senior scientist at New England Aquarium told the Washington Post in an interview last October.

The Gulf of Maine Research Institute announced in September, the Gulf is warming “at a rate that is four times faster than that of the world’s oceans, as a whole.”

According to an October 2021 report from New England Aquarium, 2010 marked the start of the recent decline in the right whale population. Researchers are trying to determine where they are and most agree the alarming warming of the Gulf of Maine could be contributing to their migration.

“It’s incredibly frustrating,” said Marianne LaCroix, executive director of the Maine Lobster Marketing Collaborative. “All the data indicates the whales are not in this area.”

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute conducts acoustic surveys listening for marine sounds indicating right and other whales. According to its website, 53 right whales were detected around Martha’s Vineyard between December 2021 and last March. During the same period, five were detected in the Gulf of Maine.

NOAA tracks right whale death by confirmed carcasses. From 2017 to August 2022, tracking showed no carcasses in the Gulf of Maine but showed right whale carcasses found in Canada and around Cape Cod. NOAA believes only about one third of right whale deaths are documented.

In creating restrictions for the lobster industry, NOAA said the biggest threat to the species’ survival is entanglement in the ropes used by lobster and Jonah crab fishermen. However, its 2021 report on right whales and the lobster industry said “It is important to consider that most right whale mortalities are never seen.”

The same report explained, “Currently, there is no way to definitively apportion unseen but estimated mortality across causes... (NOAA) assumed that half of the estimated undocumented incidents occurred in U.S. waters and were caused primarily by incidental entanglements.”

Sen. Angus King stated in his remarks to the U.S. Senate on Dec. 21, no right whale deaths were ever attributed to Maine lobster gear and no right whales were entangled in Maine lobster gear in the past 20 years.

And that seems to be the central question: If right whales aren’t present in the Gulf of Maine and if most of the deaths are unseen, how do we know what is causing their dwindling numbers?

“The fishery is required to prove a negative,” LaCroix explained. “The other problem with this is it focuses on the lobster industry. They aren’t saving the whales by focusing on an industry that’s not harming the whales.”

“If you eliminated the Maine lobster fishing industry it wouldn’t change a thing for the right whales,” Farrin said.

No to lobster fishing; yes to wind

According to its website, aside from commercial fishing, NOAA authorizes the “incidental take (death) of marine mammals,” primarily for construction, oil and gas production and renewable energy activities creating sound underwater and authorizations are for harassment, serious injury, or mortality of marine animals.

October’s draft right whale (NARW)and offshore wind (OSW) strategy created by NOAA and the Bureau of Energy Management explains areas proposed for this development in the U.S. are those where right whales ““...engage in migration, foraging, socializing, reproductive, calving, and resting behaviors critical to their survival.”

“It is important to recognize that NARWs migrating along the U.S. Atlantic Coast travel through or nearby every proposed OSW development,” the draft strategy explains.

It also identifies offshore wind development activities and stressors potentially affecting right whales. Among these are noise, “entanglement ... from floating wind turbines, cables, moorings” and “increased risk of strikes from vessels involved in OSW projects,” two of the most frequently cited threats to the right whale population.

In July, NOAA granted an incidental harassment authorization to Vineyard Northeast, LLC “to incidentally harass, by Level B harassment, marine mammals” despite concerns raised by Oceana, an ocean advocacy group.

This spring, the company will begin construction of its offshore wind farm 15 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard, according to a report by Cape and Island NPR in 2021.

Morley expressed frustration with the seemingly inconsistent NOAA positions. “The New England Aqua Ventus Project (off Monhegan) lies in the middle of the LMA1 closure area,” he said. LMA 1 was restricted to lobster and Jonah crab fishermen for part of the year to protect right whales.

Plummer agrees. “How is it OK for windfarms to interfere with the whales’ migration pattern?”

What’s ahead

“It’s a reprieve,” said Farrin of the pause created by Congress. But what will happen in coming years is undetermined.

“The average lobsterman is 57 with a mortgage, a truck and maybe 12,000 hours on his boat’s engine.” Farrin explained. “He might have been thinking about re-building his engine. Now, he’s thinking twice.”

First National Bank’s Nicholson said they are keeping an eye on the regulations, explaining this is not just business. “It’s much more personal. A lot of us have friends in the industry.” He applauded everyone who worked to bring about the pause.

Uncertainty about the fishery’s future troubles its members. “It’s hard not knowing what the future will bring,” Morley said. “You invest into an industry that may not be around.”

Plummer pointed out the lobstermen still need to win their appeal of the recent NOAA regulations. “We’ve been in this spot now with the unknown hanging over our heads, investing in a business and you don’t know what that business will be in six years.”

Will the pause help to secure a fishery that has been a way of life for generations? Most lobstermen acquired their skills as youngsters aboard a father or grandfather’s boat, as did Plummer and Morley.

Ironically, right whales and Maine’s lobster fishery may be facing similar outcomes.

As Nick Page said, “Maine lobstermen are the stakeholders in the Gulf of Maine.”