Behind the silver screen at Harbor Theater

Diane Demetriades welcomes moviegoers to the concession stand Dec. 19 during Harbor Theater's premiere showing of "Wicked: For Good." ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Diane Demetriades welcomes moviegoers to the concession stand Dec. 19 during Harbor Theater's premiere showing of "Wicked: For Good." ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Reel to reel movie projectors are a thing of the past. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Reel to reel movie projectors are a thing of the past. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Projectionist Emily Gosselin prepares for showtime. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Projectionist Emily Gosselin prepares for showtime. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Older films arrive in hard drives that are digitally uploaded to the theater's systems. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Older films arrive in hard drives that are digitally uploaded to the theater's systems. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Can't forget popcorn! ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Can't forget popcorn! ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Executive Director Lynn Thompson talks longevity of community theater. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Executive Director Lynn Thompson talks longevity of community theater. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Diane Demetriades welcomes moviegoers to the concession stand Dec. 19 during Harbor Theater's premiere showing of "Wicked: For Good." ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Diane Demetriades welcomes moviegoers to the concession stand Dec. 19 during Harbor Theater's premiere showing of "Wicked: For Good." ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Reel to reel movie projectors are a thing of the past. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Reel to reel movie projectors are a thing of the past. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Projectionist Emily Gosselin prepares for showtime. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Projectionist Emily Gosselin prepares for showtime. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Older films arrive in hard drives that are digitally uploaded to the theater's systems. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Older films arrive in hard drives that are digitally uploaded to the theater's systems. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Can't forget popcorn! ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Can't forget popcorn! ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register Executive Director Lynn Thompson talks longevity of community theater. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

Executive Director Lynn Thompson talks longevity of community theater. ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay Register

ISABELLE CURTIS/Boothbay RegisterThe film industry is an equation. There's the director with a vision, the crew who make it come to life, and the audience members who hang on the edge of their seats, but there's an often overlooked variable: the regional cinemas that disperse that movie magic to the masses.

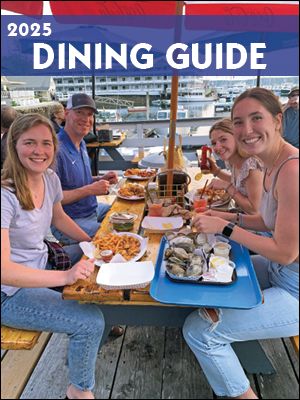

Although existing in some form at the Meadow Mall since the 1980s, the Harbor Theater, as it's known today, gained non-profit status in 2017 and continues to show new releases, indies, documentaries and fan favorites with the help of its 14 part-time employees.

According to Executive Director Lynn Thompson, about half of the theater’s revenue is generated from a mix of donations, memberships and contributions from community partners, totaling about $150,000 in 2024. The other half is earned from tickets and concessions. This affords the organization more curation freedom, as they aren't beholden to ticket sales for funding.

So, how do they decide what ends up on screen? It’s a mix of keeping up with industry news, a booking agent who advises which films might be a good fit for the community’s older population and viewer suggestions.

Sometimes this means skipping a big box-office horror flick for a smaller historical drama, such as "Downton Abbey," which has been widely popular in the region. Thompson has also found success in playing Netflix’s limited theatrical releases despite their upcoming or overlapping availability on streaming.

“Not many (older audience members) have streaming platforms, or they don't watch them that much. We can show something after it's already gone to streaming and (still) have as good a crowd,” she said.

Community demographics also decide how long a movie sticks around. Licensing is complicated and depends on the distributor, but picking up a film during its wide-release date, or “on the break,” comes with a requirement to show it for two or three weeks, Thompson explained. This is why Harbor Theater will often acquire a film later in its release when the requirement is lower.

“In the summertime, we're more likely to take a blockbuster on the break and run it for (three) weeks, because we've got all those tourists in town ... But with our own population, if you're running something for three weeks, then you're down to two people in the audience.”

Not only would this take up airtime the cinema could devote to other releases, it's not profitable. Distributors take a portion of ticket sales, usually between 35% and 50%, or if it's a Disney product, 50%-56%. Sometimes studios don’t decide what percent they’re taking until after seeing how well the film sold, said Thompson.

Even a one-time showing of a classic film costs a flat rate. For instance, the recent holiday showing of "Elf" (2003) cost $150, whereas "Lawrence of Arabia" (1962) was $375.

These older films come as a hard drive, similar in size to a VHS tape, whose contents are uploaded digitally to the theater’s systems. As for the big-budget blockbusters, one may imagine they come guarded under lock and key to prevent any opportunists from leaking their contents to the internet, but not so. They arrive via email.

But it isn't as simple as downloading and hitting play. Tech Director Robert Jordon spends an hour running the film on the projector, which can range in price from $50,000 to $100,000, to adjust sound and lighting levels to make sure everything is ready for opening night. A playlist is also created, so the announcements, trailers and film are all in one place.

It’s a labor of love for an industry that has been in the news often, with headlines about cinemas closing, the risk of at-home viewing's popularity, and streaming giant Netflix's entering a bidding war for Warner Bros. Studios.

But these dire predictions are the opposite of reality for community theaters, which have become hubs for socialization, said Thompson. This togetherness is further fostered by Harbor Theater’s variety of programming, which makes attendance a unique, communal experience, such as their “Lunch with a Classic” series that offers viewers a movie-themed meal, or the curated roster of offbeat flicks shown at Tanner Grover’s Cinema Clubhouse.

The films and documentaries sponsored by the theater’s community partners also give residents a peek into the issues that affect the region that other nonprofits are passionate about.

“I think as long as there is a demand for education, enrichment and entertainment then no matter how much things go to streaming, communities will still respond to coming together to watch things.”