Nanotags and Motus Uncovering Secrets of Bird Migration

Last year in this column we briefly mentioned something called the Motus Wildlife Tracking System that is among the new technologies revolutionizing the study of animal movements. Motus (the Latin word for “movement”) is a project that is coordinated through the nonprofit bird research organization Bird Studies Canada. The project uses tiny radio tags, called nanotags. The nanotags are so small that even a bird as small as a warbler can carry one without impairing its ability to fly, find food, and evade predators. In fact, some nanotags are so small that they have been placed on dragonflies and butterflies to track their movements and activity.

Each nanotag transmits on the same radio frequency but sends out the signal using different rates and numbers of pulses, a bit like an old Morse Code signal. Small radio antenna receivers can be set up with tiny built-in computers that continuously collect information about each radio signal that comes within its 5-10 mile range. Researchers can, at intervals, download all the data and see the dates and times that individual nanotag signals were registered by the receiver.

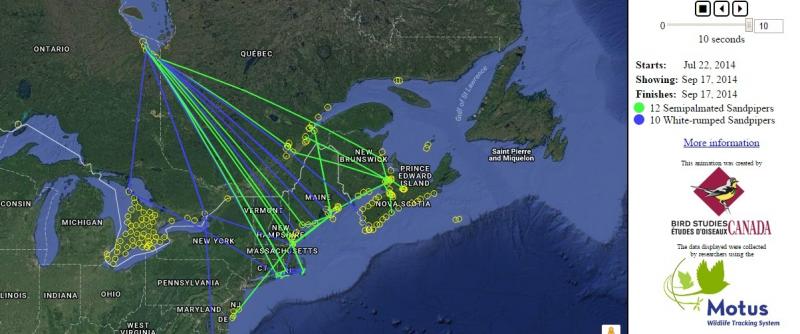

What makes the Motus project particularly powerful is that there are now more than 100 receiving stations established that span from far northern Canada to northern South America. The northeastern U.S. and southeastern Canada have a particularly high concentration of Motus receivers. Researchers in Maine have embraced the technology for a number of years, so our state has at least a dozen Motus stations.

Some of the findings are pretty incredible.

In 2015 and 2016, ornithologists placed nanotags on Swainson’s thrushes and gray-cheeked thrushes in Colombia while the birds were there on the wintering grounds. In spring, the birds were detected along their migratory pathways in multiple locations extending far north into Canada. In spring 2016 one of these birds, a gray-cheeked thrush, was detected on its way north right here in Maine.

Scientists working at Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge in Wells, Maine placed nanotags on saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrows, a highly specialized bird species that, as its name suggests, spends its entire life in saltmarshes. These birds were tracked in fall migration at saltmarshes along the coasts of Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Virginia.

Semipalmated sandpipers, white-rumped sandpipers, and red knots that were captured and affixed with nanotags on the coast of Canada’s James Bay in the fall were discovered to have made overnight flights to the Maine coast and other New England coastal stopover sites.

Nanotags placed on common terns and black guillemots in the Gulf of Maine have helped identify the most important offshore feeding sites for these birds and showed timing of foraging trips and feeding of young.

One of the big-picture findings that all of this exciting new migration and movement research is uncovering is that birds use much more of our land and seascape then we ever realized. That also means that we have a greater responsibility to protect a lot more of our natural habitats than we might have realized if we want to ensure the birds and a healthy environment will be art of our future for generations to come. You can read more about new bird migration research technologies at: http://www.borealbirds.org/sites/default/files/pubs/Report-Charting-Healthy-Future-Birds.pdf.

Jeffrey V. Wells, Ph.D., is a Fellow of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Dr. Wells is one of the nation's leading bird experts and conservation biologists and author of the “Birder’s Conservation Handbook.” His grandfather, the late John Chase, was a columnist for the Boothbay Register for many years. Allison Childs Wells, formerly of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is a senior director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, a nonprofit membership organization working statewide to protect the nature of Maine. Both are widely published natural history writers and are the authors of the book “Maine’s Favorite Birds.”

Event Date

Address

United States