Rollin’ on the river

As far as I could tell, the documentary film for which I was being asked to provide the voice-over narration seemed like just one more high-minded “art piece” destined to appeal to a microscopically thin slice of the demographic pie: a project with just about zero commercial potential.

I mean, how much cinematic excitement can you expect from a grainy, black and white “home movie” of some back woods Maine logging operation in 1930?

Yet, despite its obvious commercial limitations, the more I learned about the film, the more intrigued I became. The initial pitch came back in 1984 during a phone conversation with my friend, David Weiss, a man I knew to be a serious filmmaker as well as an enthusiastic cultural historian.

I’d met David and his partner, Karan Sheldon, a couple of summers earlier when they dropped by a project I was working on at the fledgling Neworld Animation Studio in Noel Stookey’s funky converted hen house in South Blue Hill.

Clearly excited about the project, David explained how a donated canister of 16-millimeter black and white film, which had been kicking around the UMO archives for several years, had recently been rediscovered by University historian David Smith.

A while later a team of academics including Smith, legendary Maine folklorist Sandy Ives, and UMO film producer Henry Nevison gradually became convinced that the long forgotten archival footage they’d stumbled upon might very well constitute “a significant artifact in Maine’s cultural heritage.”

Shot in the summer of 1930 by lumber mill owner Alfred Ames, the film does indeed capture, in wonderful detail, the exact methods used by Ames’ crew of local Maine woodsmen, conducting what would turn out to be the last long-logging operation on the Machias River.

Despite its potential historical significance, several obstacles would need to be overcome in order to complete the film, not the least of these being financial in nature. Simply put, the long journey from dusty university archive to silver screen was going to require some serious dough.

Fortunately, the funds eventually materialized by way of a creative public/private partnership, which included The Maine Humanities Council, UMO and Champion Paper in Bucksport.

By the time I came on board, the film was nearly complete. The only thing missing was the soundtrack. As originally presented in grange halls and opera houses throughout rural Maine, the silent film had been accompanied by live narration provided by Alfred Ames himself!

Having located a copy of Ames original script, all the producers needed was a narrator capable of recreating the original script in an authentic, era-appropriate Downeast dialect. Everyone agreed that I was the right man for that job.

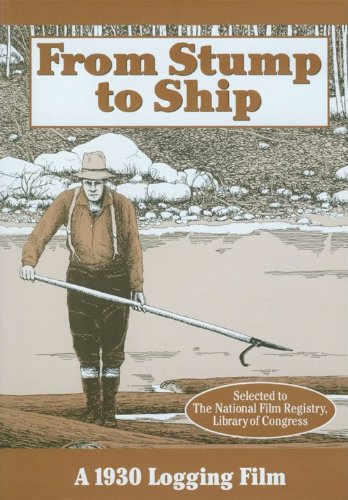

During a lunch break at a local Portland eatery near the recording studio, David broached the subject of royalties. It was generally accepted that the documentary (which by then had gained the official title, "From Stump to Ship") was for all intents and purposes a “labor of love” with little or no commercial potential.

However, in the unlikely event that our film ever did show a profit, David wondered, what sort of royalty I’d consider fair compensation for my contribution.

Hey, you don’t ask, you don’t get right? Plucking a rather hefty pie-in-the-sky number out of thin air, I shared it with David. We shook hands, finished our lunch and headed back to the studio to complete the soundtrack. Nobody was prepared for what happened next.

At From Stump to Ship’s “world premier” held on Sept. 20, 1985 in a 600-seat auditorium on the UMO campus, we’d have been happy to see even half of the seats filled.

Imagine our shock when nearly 1,200 film-goers showed up to view our modest, half-hour-long black and white logging documentary.

And that was only the beginning. There were similarly large, enthusiastic crowds at all 20 or so screenings we held across Maine that fall. A broadcast of the film on Maine Public Television caught the attention of PBS network brass and the rest, as they say, is “history.”

In 2002, "From Stump to Ship" was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress. Against all odds, the film had also become a solid commercial success.

The movie’s surprising popular appeal helped Sheldon & Weiss establish Northeast Historic Films in Bucksport. And even my modest cut of the profits managed to generate enough cash to purchase a half decent used skidder.

But the real payoff had nothing to do with money. Knowing that long after I’m gone, I’ll still be heard sharing an important part of Maine’s history with future generations and, well, that’s something that no amount of money can buy.

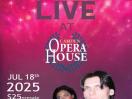

Event Date

Address

United States