Lighthouse on Negro Island?, Part I

These four houses in 1995 at Greenleaf Lane off Commercial Street are: 1) present day Admiral's Quarters, 2) Pal Vincent's house, 3) small house behind Pal, 4) present day Greenleaf Inn. These overlapping shots will be referred to in a later article, so readers may wish to retain this article. Courtesy of Boothbay Region Historical Society

These four houses in 1995 at Greenleaf Lane off Commercial Street are: 1) present day Admiral's Quarters, 2) Pal Vincent's house, 3) small house behind Pal, 4) present day Greenleaf Inn. These overlapping shots will be referred to in a later article, so readers may wish to retain this article. Courtesy of Boothbay Region Historical Society

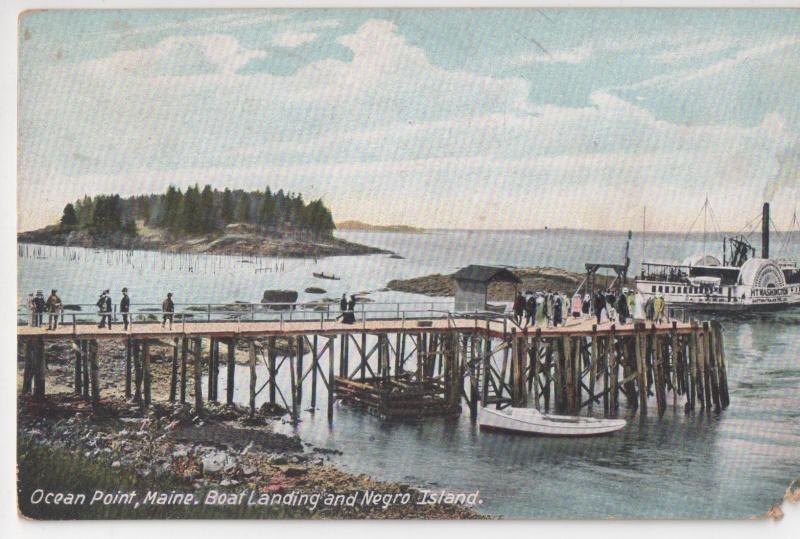

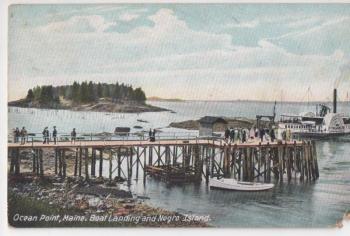

This color postcard of Negro Island from about 1905 shows Melvin Sawyer's fish weir in disrepair. There are brownish camps on the island tip, though readers may be unable to make them out. The image is an example of early photoshopping. The side-wheeler steamer Mt. Washington, built 1872, never left Lake Winnepasaukee in her 67-year career. Courtesy of Boothbay Region Historical Society

This color postcard of Negro Island from about 1905 shows Melvin Sawyer's fish weir in disrepair. There are brownish camps on the island tip, though readers may be unable to make them out. The image is an example of early photoshopping. The side-wheeler steamer Mt. Washington, built 1872, never left Lake Winnepasaukee in her 67-year career. Courtesy of Boothbay Region Historical Society

These four houses in 1995 at Greenleaf Lane off Commercial Street are: 1) present day Admiral's Quarters, 2) Pal Vincent's house, 3) small house behind Pal, 4) present day Greenleaf Inn. These overlapping shots will be referred to in a later article, so readers may wish to retain this article. Courtesy of Boothbay Region Historical Society

These four houses in 1995 at Greenleaf Lane off Commercial Street are: 1) present day Admiral's Quarters, 2) Pal Vincent's house, 3) small house behind Pal, 4) present day Greenleaf Inn. These overlapping shots will be referred to in a later article, so readers may wish to retain this article. Courtesy of Boothbay Region Historical Society

This color postcard of Negro Island from about 1905 shows Melvin Sawyer's fish weir in disrepair. There are brownish camps on the island tip, though readers may be unable to make them out. The image is an example of early photoshopping. The side-wheeler steamer Mt. Washington, built 1872, never left Lake Winnepasaukee in her 67-year career. Courtesy of Boothbay Region Historical Society

This color postcard of Negro Island from about 1905 shows Melvin Sawyer's fish weir in disrepair. There are brownish camps on the island tip, though readers may be unable to make them out. The image is an example of early photoshopping. The side-wheeler steamer Mt. Washington, built 1872, never left Lake Winnepasaukee in her 67-year career. Courtesy of Boothbay Region Historical Society

I wrote four articles about Negro Island in 2010 and 2011 outlining its ownership over the centuries and the origin of its name. I'll continue with Negro by describing the reason I did exhaustive research on the island. These articles show (for the umpteenth time) the frailty of human memory and the fascinating, but lengthy timesink of research.

Bobby Boyd of Boothbay Region Greenhouses asked me in June 1994 if I'd heard of a lighthouse on Negro Island. I laughed and put the notion in my personal category of fantasized or romanticized subjects. There of course was no official lighthouse on Negro, for they are well documented. But people had created their own lighthouses or informal navigational structures—sometimes nothing more than a lantern on a stick, sometimes whimsical structures fashioned after a imaginative notion. But I told Bobby I would check into it, so I called his source, Pal (Mrs. Parker) Vincent of Greenleaf Lane in Boothbay Harbor.

Ken Merrill

When I visited Pal Vincent, her story was a little fragmented because it was told to her in passing 23 years before she told me 22 years ago. When she and Parker settled in the Harbor, they used Ken Merrill as their plumber. According to Pal, Ken marveled that he "helped" move the house when he was five years old, and that he was now back, working on it again. He said it had been moved from Negro Island where it had been a lighthouse that had burned and that his grandfather had moved it.

Pal's house had an old-time summer cottage feel, though parts looked younger. It seemed small to support a tower, but I looked carefully for any sign of a floored-over opening that might indicate one. No sign, though if the "lighthouse" part burned off, maybe that accounted for both no sign and the newness. Pal said she might run across something else that would help.

Ken Merrill would have been five in 1911, and I recalled that Clem McCobb, the major local late 1800s house mover, was his step-grandparent. I knew Clem had died in 1912—so far so good. I knew also that Ken, when grown, had worked moving houses for Milton Giles, a major 20th-century house mover. Things just might come together.

Giles Movers

I went up to Giles Hill and asked Red Giles, Milton Giles's oldest son, about Clem's or any move to the Greenleaf Lane area. We went through again a move Red told me about in 1989, one his father made from the water up across Commercial Street by the current site of Tugboat Inn. That move was before Red started moving houses with him in 1927, but much later than 1911.

The Giles crew was in the process of bringing the house up from the shore. When a house was moved a short distance back then, it was moved on rollers with tackles (long land distances would have been with oxen). Men crawled in and out, under and beside the house, canting the rollers with a blow of a mall or pulling them out and bringing them forward, as the building inched ahead toward the motive power, a horse and a windlass (actually a capstan). This move was typical of all others, attracting a crowd to watch the spectacle.

Fred Greenleaf, for whom Greenleaf Lane was named, was walking home, took in what was up, and lit into the crowd for not warning the crew of a dangerous situation developing. Fred saw that the staked bars anchoring the windlass were coming loose and that if something wasn't done, the house would roll backwards down the hill, crushing the men. He alerted Milton and the crew quickly trigged the rollers and restaked the bars. Milton never forgot Fred's action while others just waited for the excitement. I asked Red where that house came from since it came by scow. He didn't know, but knowing the gap between the buildings there, the house had to be small. I asked him who Milton did the job for; he said it would come to him. Piecing history together takes time.

Dry Sources

In the next few months, I visited a number of people to ask about the move or any odd structures on Negro. Ken Merrill's widow, Helen Alley Merrill, had no memory of a move from Negro or to Greenleaf Lane. Irving Blake of Boothbay Center, the oldest surviving member of Milton Giles' crew, didn't remember such a move — not unusual when you consider the huge number of houses that were moved in earlier decades. Murray descendant Dot Rice Booth remembered Pete the Indian's tent on Negro when she'd go out with Murray relatives in the 1910s, but no lighthouse. Hazel McCobb Poore and Winfield Dodge, down on Linekin Neck, were stumped; and my usual Harbor sources, retired lawyer Asa Tupper and Lester Barter, as well as Mildred Webster, a neighbor of Pal's, couldn't shed any light on the mystery move or the "lighthouse." Mildred suggested Butler Eames. When I visited him, he confirmed that Pal's house came from Negro Island after World War I.

My progress in late summer 1994 was adding more confusion. Did Ken Merrill mix up observing his grandfather move the house with a later job for Milton Giles? Or did Pal jumble the stories? And no more word of a strange structure on Negro. It was time to go to documents and hope for a mention.

Insurance Maps and Deeds

The Sanborn Insurance maps are great for the study of built-up parts of Boothbay Harbor. We have maps from 1885 to 1949. I found that Pal's house had not appeared by 1911, nor had it arrived by 1922. It is shown on the next map, the 1931 version—so it appeared between 1922 and 1931. Clem McCobb didn't move it when Ken was five.

Next I went to the courthouse to trace Negro's deed chain. Two prior articles described the ownership from the 1700s to about 1950 and the morass of claims on the island, complete with multiple quiet title actions. Given my limited knowledge at that time (1994), one name seemed helpful: Stephen Sawyer of present Lincoln Street, East Boothbay bought the island in 1832 and held it for a few years. I knew his son Billy and grandsons Melvin and Billy ended up in the lower Commercial Street area. Was that the connection? I couldn't know I was only beginning. Next time: Hunting and pecking for the Negro-McFarlands Point connection and the "lighthouse."

————-

Do you enjoy these articles? Consider becoming a member of the historical society and support such activity! Membership dues are $15 for an individual; $25 for a family; and $50 for a contributing membership. Checks may be sent to BRHS, P. O. Box 272, Boothbay Harbor, ME 04538, or drop in the museum at 72 Oak Street in the Harbor, Thursday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

Event Date

Address

United States