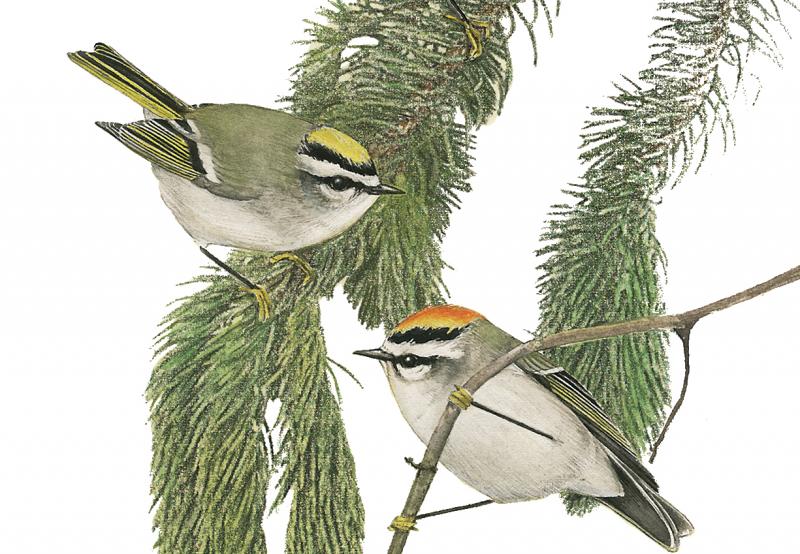

Christmas Tree Birds

The golden-crowned kinglet is the quintessential “Christmas tree bird” because it spends most of its life within the branches of coniferous trees like balsam fir, spruce, and hemlock. (Golden-crowned kinglet painting by Evan Barbour from the book,”Maine’s Favorite Birds,” by Jeff and Allison Wells, courtesy of the authors)

The golden-crowned kinglet is the quintessential “Christmas tree bird” because it spends most of its life within the branches of coniferous trees like balsam fir, spruce, and hemlock. (Golden-crowned kinglet painting by Evan Barbour from the book,”Maine’s Favorite Birds,” by Jeff and Allison Wells, courtesy of the authors)

The golden-crowned kinglet is the quintessential “Christmas tree bird” because it spends most of its life within the branches of coniferous trees like balsam fir, spruce, and hemlock. (Golden-crowned kinglet painting by Evan Barbour from the book,”Maine’s Favorite Birds,” by Jeff and Allison Wells, courtesy of the authors)

The golden-crowned kinglet is the quintessential “Christmas tree bird” because it spends most of its life within the branches of coniferous trees like balsam fir, spruce, and hemlock. (Golden-crowned kinglet painting by Evan Barbour from the book,”Maine’s Favorite Birds,” by Jeff and Allison Wells, courtesy of the authors)

Like a great many Mainers, we have a Christmas tree up now in our living room that we picked up at an Edgecomb Christmas tree farm a few weeks ago. It is decorated with colored lights and a delightful accumulation of memories and family history in the form of dozens of ornaments of every shape, size, and color.

Most readers will not be surprised to know that among those ornaments are representations of birds. There are ceramic snowy owls, knitted barred and great horned owls, paper whooping cranes and toucans, a felt red-headed woodpecker and a number of carved and painted wooden ornaments of various species. These wooden ornaments are made by a local craftsperson who we see at several craft shows every season and from whom we have gotten into the habit of buying at least one new bird species every year. From this clever person’s collection of bird ornaments we have a flying tern, a loon, a yellow warbler, a Baltimore oriole, a robin, a bluebird, a common goldeneye, a bald eagle, a snowy owl, and an evening grosbeak.

But one bird species we are missing from our Christmas tree is perhaps the one that would be the most fitting to see there: the golden-crowned kinglet.

Why?

Because the golden-crowned kinglet is a bird that spends most of its life within the branches of the kinds of trees that people use for Christmas trees, coniferous trees like balsam fir, spruce, and hemlock. And despite being only slightly larger than a hummingbird and decidedly smaller than a chickadee, golden-crowned kinglets spend the winter here in Maine. People who know there birds mainly from what they see at their feeders may be surprised to learn that golden-crowned kinglets can be found in winter in Maine. That’s because these diminutive birds never frequent bird feeders. They find all their food by searching for insects, and insect eggs, on the bark, branches, and needles of trees, occasionally perhaps consuming a small seed now and then.

A great mystery is how they can survive the long nights during particularly cold periods of mid-winter. Researchers have calculated that they would need to eat 2-3 times their weight in food to maintain their core body temperature. That would be hard enough but then what do they do during a long night when they can’t find food for 12 hours or more? Apparently they sometimes huddle together for warmth in little protected spots during those winter nights, but much remains to be learned about their secrets for survival.

One thing that is certain is that golden-crowned kinglets often lay a lot of eggs, sometimes as many as 10 or more. This is unlike most birds their size, which typically only lay 3-5 eggs. This may be a strategy that evolved precisely because many kinglets die during those harsh winter months.

But luckily for all of us, a walk through a snowy grove of spruce-fir on a cold day in December or January will often be rewarded with the cheery, high-pitched “seet-seet-seet” calls of a small flock of these remarkable birds. A sighting of one in a snow-adorned natural “Christmas tree” showing off its golden crown will be a holiday gift that you will long remember!

Jeffrey V. Wells, Ph.D., is a Fellow of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Dr. Wells is one of the nation's leading bird experts and conservation biologists and author of the “Birder’s Conservation Handbook.” His grandfather, the late John Chase, was a columnist for the Boothbay Register for many years. Allison Childs Wells, formerly of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is a senior director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, a nonprofit membership organization working statewide to protect the nature of Maine. Both are widely published natural history writers and are the authors of the book, “Maine’s Favorite Birds” and the just-released “Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao.”

Event Date

Address

United States