The Birth and Rebirth of the Hendricks Head Lighthouse

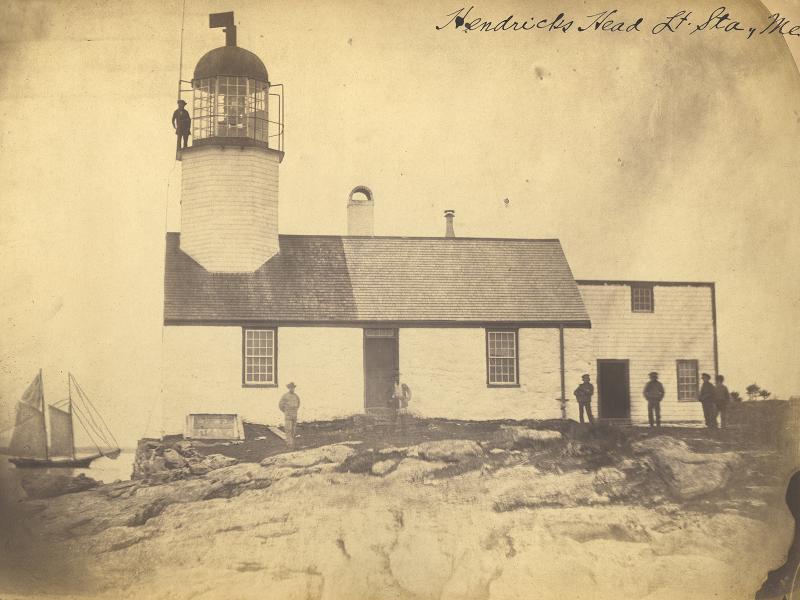

Built on a seawall at the water’s edge, this is the oldest known photograph of Hendricks Head’s 1829 lighthouse and keeper’s dwelling. Courtesy of National Archives

Built on a seawall at the water’s edge, this is the oldest known photograph of Hendricks Head’s 1829 lighthouse and keeper’s dwelling. Courtesy of National Archives

Hendricks Head Light Station circa 1890. Left to right: boathouse, barn for horses, dwelling, lighthouse and bell tower. Courtesy of National Archives

Hendricks Head Light Station circa 1890. Left to right: boathouse, barn for horses, dwelling, lighthouse and bell tower. Courtesy of National Archives

USA Stars & Lights: Portraits from the Dark features this photo of Hendricks Head Light as one of its 160 lighthouses. (starsandlighthouses.com) Courtesy of David Zapatka

USA Stars & Lights: Portraits from the Dark features this photo of Hendricks Head Light as one of its 160 lighthouses. (starsandlighthouses.com) Courtesy of David Zapatka

Built on a seawall at the water’s edge, this is the oldest known photograph of Hendricks Head’s 1829 lighthouse and keeper’s dwelling. Courtesy of National Archives

Built on a seawall at the water’s edge, this is the oldest known photograph of Hendricks Head’s 1829 lighthouse and keeper’s dwelling. Courtesy of National Archives

Hendricks Head Light Station circa 1890. Left to right: boathouse, barn for horses, dwelling, lighthouse and bell tower. Courtesy of National Archives

Hendricks Head Light Station circa 1890. Left to right: boathouse, barn for horses, dwelling, lighthouse and bell tower. Courtesy of National Archives

USA Stars & Lights: Portraits from the Dark features this photo of Hendricks Head Light as one of its 160 lighthouses. (starsandlighthouses.com) Courtesy of David Zapatka

USA Stars & Lights: Portraits from the Dark features this photo of Hendricks Head Light as one of its 160 lighthouses. (starsandlighthouses.com) Courtesy of David Zapatka

Why Build a Lighthouse on the Sheepscot River?

In the early 1800s, mariners involved in fishing and maritime trade were in need of a navigational aid to guide them safely in and out of the Sheepscot River. This commercially important waterway was their vital link between the Gulf of Maine and the inland port of Wiscasset, a town recognized at that time to be the busiest seaport north of Boston. Just fifteen miles upriver, a deep and sheltered harbor formed the hub of a prosperous trade center renowned for shipbuilding, lumber, and fish.

Rough seas, frequent fog, and submerged ledges in the outer Sheepscot Bay were elements that posed tremendous threats to transport vessels and fishing boats. Hence, sea captains, fishermen, and businessmen alike petitioned the Federal government for a lighthouse. In 1828, President John Quincy Adams, and his administration, responded to their plea by authorizing $5,000 to build a beacon that would facilitate the safe and reliable movement of vessels both entering and leaving the Sheepscot River.

Why Was Hendricks Head Chosen as the Lighthouse Site?

At the wide mouth of Sheepscot Bay, Southport Island forms the river’s eastern boundary, while Georgetown Island forms its western border. Located about halfway up Southport’s shore, a promontory named Hendricks Head was selected as the perfect site. If a lighthouse were erected on Hendricks Head, vessels south of Seguin Island Light would be able to travel a northeast course until they saw its light in the distance. A course change to due north would allow them to clear the nearby dangers of Tom’s Rock, Black Rocks, the Sisters, Cat Ledges, and Griffith Head Ledge.

In the 1845 American Light-House Guide, author Robert Mills described the navigational route as such: “If bound up the Sheepscot River passing Seguin Light to the southward, steer N.E. until you bring Hendricks Head Light to bear N., a little westwardly, then run for it, keeping a starboard shore close aboard.”

Who was the Person Named Hendricks?

Who was the person associated with not only the name of the lighthouse, but a harbor, road, hill, and museum - all on Southport Island? According to the Lighthouse Friends’ website, it appears that in 1735 Nathaniel Hendricks swapped his land holdings in Arundel for property on Southport, presumably Hendricks Head. A call to Barbara Rumsey of the Boothbay Region Historical Society verified that indeed he was once a resident of Arundel (1726-1737), and at a later date may have resided on Fisherman’s Island, as records show he petitioned land developer Kennebec Proprietors for a lease in 1751.

What Did the First Hendricks Head Lighthouse Look Like?

On April 23, 1829, Maine’s Lighthouse Superintendent John Chandler oversaw the government’s purchase of the nine-acre, twenty-rod property owned by Jonathan Pierce for $200. The following month his detailed request for proposal (RFP) to build the Hendricks Head Lighthouse was advertised.

The RFP described the construction requirements as: “The dwelling house to be built of suitable, split, undressed stone, forty feet by twenty, one story, eight feet in the clear, and the walls to be twenty-four inches thick.” At one end, the keeper’s dwelling was to include an attached 14 x 12 foot kitchen or porch and a surmounted lighthouse. The tower’s specifications were: “On one end of the house to be an octagon tower of ten feet in diameter, to stand on the beams of the house, to rise eight feet above the ridge of the house.” The tower was then topped with a glass lantern of the early birdcage design, one that consisted of 168 panes of glass.

When was the Hendricks Head Lighthouse First Lit?

A building contract for $2,662 was awarded to Joseph Berry, one of Maine’s widely-used, lighthouse contractors. A separate agreement was signed with Winslow Lewis to outfit the tower with its lighting apparatus. The RFP stated: “…eight patent lamps and eight fourteen-inch reflectors, and to have eight ounces of pure silver in each reflector, to be placed on two circles, four on each.” On December 1, 1829, Keeper John Upham lit those eight, parabolic-reflector lamps for the very first time.

Why was a Second Lighthouse Built in 1875?

In 1875, the U.S. Lighthouse Board’s Annual Report painted this grave picture of the 46-year-old structure: "It is now in such an advanced state of dilapidation and decay that it has become uninhabitable.” It’s possible that contractor Berry failed to follow Supt. Chandler’s mortar-mixing instructions of good lime, fresh water, and sand that hadn’t been exposed to saltwater.

During construction, Keeper Jaruel Marr reported the building timeline in his logbook as such: On June 29, 1875, “Engineers arrived and surveyed the ground with reference to building a new tower and keeper’s dwelling.” On July 4, 1875, “Arrived and commenced to clear away the old buildings and erect new ones.” On July 21, 1875, “Steamer Myrtle with lumber and building material.” On September 23, 1875, “Shifted the lense from the old tower to the new tower and lighted up the new for the first time.”

Who Kept the Light Prior to Decommissioning?

The Hendricks Head logbook entry of July 1, 1895 was written by Keeper Marr’s successor and it read: "Arrived at this station at 2 PM to relieve Mr. Jaruel Marr, who has been keeper here for the past 29 years." This new steward was none other than Jaruel’s son Wolcott. One can only imagine how happy he must’ve been to share his childhood home with his wife and nine children. For 35 years, Keeper Wolcott Marr faithfully served the mariners and lovingly cared for the light station until his 1930 death.

A long-time employee of the U.S. Lighthouse Service, Charles L. Knight was Hendricks Head’s final lighthouse keeper. Three years after his arrival, the government decided to decommission ten of Maine’s lighthouses as a cost-saving measure and Hendricks Head was on the list. During Keeper Knight’s tenure, many interesting events took place, with the most newsworthy being the unearthing of a skeleton from the nearby shell midden; the rescue of a couple, thanks to his dog Shep; and the recovery of a drowned lady with flatirons around her neck.

Rebirth and Restoration of the Lighthouse

Sold into private ownership in 1935, Dr. William P. Browne’s offer of $4,100 was accepted as the highest bid. The lighthouse remained dark until Dr. Browne brought electricity to the peninsula in 1951. On February 14th of that year, he signed an agreement with the U.S. Coast Guard to relight the tower. It said: "Changing conditions in maritime traffic have made it desirable to re-establish a light at this location as an aid to navigation.” It appears that the increased traffic was associated with tankers delivering oil to the fuel-powered, electric-generating plant in Wiscasset.

In 1975, Dr. Browne’s daughter Mary, and her husband Gil Charbonneau, winterized the dwelling for their year-round home. In 1991, Ben and Luanne Russell of Alexander City, Alabama purchased and restored the property and it remains their private residence today.

Fishermen, mariners, and summer sight-seers continue to enjoy the beauty, charm, and function of the Hendricks Head Lighthouse, one that safely guides their passage up and down the Sheepscot River. Lighthouse lovers can view and photograph this spectacular lighthouse from land at the Hendricks Head Beach in Southport.

Science teacher and retired Education Director at the DMR, Elaine Jones has been recognized for her vision, dedication and 30 years of public service. She designed the Maine State Aquarium and acquired/repurposed Burnt Island Light Station, where students, teachers and visitors alike shared hands-on learning through interactive exhibits and living history programs. Her passion for teaching continues as founder of the nonprofit Lighthouse Education & Nautical Studies (LENS).