Author Colin Woodard discusses new American history book

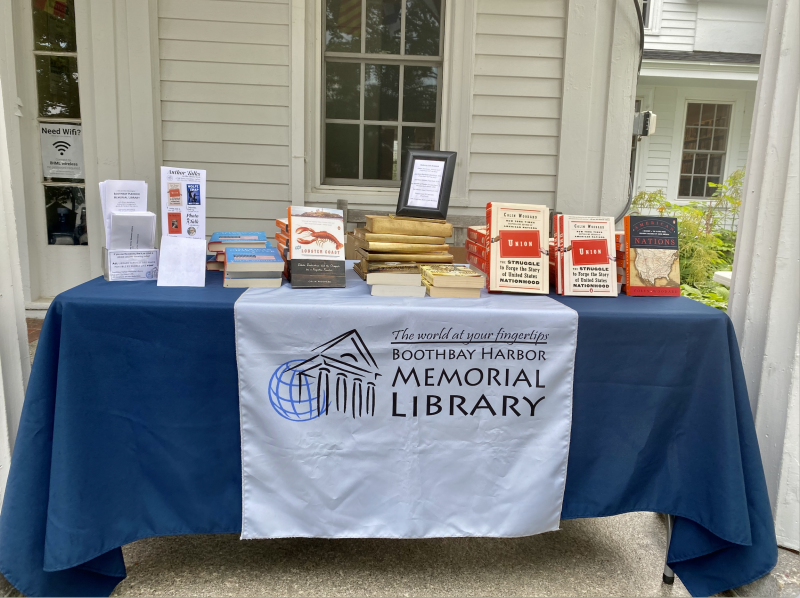

The U.S. “might not remain a unitary state,” journalist and best-selling author Colin Woodard told an audience of about 50 July 16 at Boothbay Harbor Memorial Library’s (BHML) first open-air book lecture.

Woodard discussed his new book “Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood.”

BHML Executive Director Joanna Breen began the event by acknowledging the indigenous people of the Wabanaki Confederacy, “the original stewards of this beautiful land we call Boothbay Harbor, who lived here, learned here and loved here long before this American story we are about to hear about to began.”

Woodard’s new book is a spiritual sequel to his 2011 release “American Nations,” which argues there has never been one America but rather several rival regions, established during colonization.

“These different colonial projects had distinct ethnographic, religious, and political characteristics. Different ideas about what the good life was about, who they were, the society they were building and the direction they sought to go,” Woodard explained. “They were separate cultures and had no idea that they would all end up one day in a continent-spanning superpower federation together.”

Woodard knew from writing “American Nations” that Americans also saw themselves as separate states through the 1860s and 1870s, so he began to wonder when this was forgotten in a favor of a “national narrative.” “We all grow up with the idea of the United States as being one place, Americans having a shared history going back into the colonial period, a promise of who we are and where we're supposed to be going.”

The formation and popularization of this national narrative is the focus of “Union.” Woodard was surprised the story didn’t start after the Civil War during efforts to unite the north and south, but decades earlier in the 1830s. During this time, the American revolutionists had died off and people were trying to define the republic’s identity without their direction.

The book follows the key figures in this debate: George Bancroft, William Gilmore Sims and Frederick Douglass.

A New England native, Bancroft was an influential historian who came up with the idea of the “civic national myth,” that what bands Americans together isn’t a shared ethnicity or place but shared values in the Declaration of Independence. He also believed it was God’s plan for America to spread these ideas. Sims, a southern writer and outspoken opponent of Bancroft, advocated for an “ethno-nationalist” system that favored Anglo-Saxons and believed slavery was a moral good. Douglass, an abolitionist and former slave, critiqued both stances. He believed in the values of the Declaration but argued they had to be fought for.

Woodard said he tried to structure the book like a novel with each figure’s story starting separately but colliding as the book goes on. He believes this is more engaging and helps readers understand how each man’s background influenced his beliefs.

The book ends with the first moment of American consensus and the “provisional victory” of Sims’ ideology in the 1912 election of Woodrow Wilson. Wilson was raised in Georgia and brought to the White House the white supremacist ideals of the region, Woodward said.

Woodard said he came to the same conclusions he did in “American Nations.”

“It seems entirely within the realm of possibility that within our lifetimes, the United States might not remain a unitary state. That's still my lesson. That complacency is foolish. The veneer of civilization is much thinner than you think it is. Institutions aren't just going to save us, those in charge aren't necessarily going to stand up. That need to be participants in it has become much clearer.”

Event Date

Address

United States