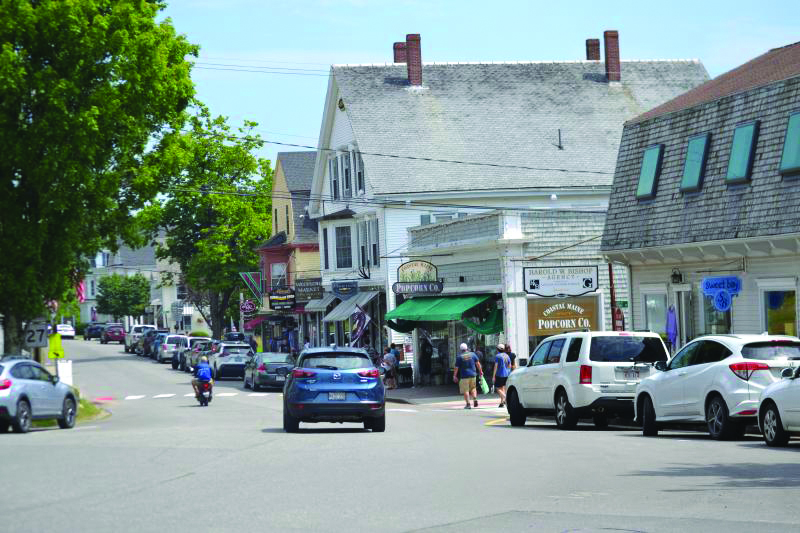

With 3 area towns on the '50 most expensive' list, what does it mean for property taxes?

Boothbay, Boothbay Harbor and Southport have made Waltham Massachusetts-based Lamacchia Realty's "50 Most Expensive Towns in Maine," published in April and based on 2023 home sales.

Southport comes in at #1 with an average home price of $1,474,231, followed by Boothbay (#21) with an average of $848,066 and Boothbay Harbor (#45) averaging $618,072.

Information from Maine Association of Realtors shows the median home price in Lincoln County is almost double the statewide number.

In this second article in a series, The Register asked, what's driving home prices? How are higher prices affecting property taxes and a town's share of state revenue?

"Nice place you have here..."

Apparently during the pandemic, the rest of the country discovered what Mainers have long known: We live in a special place. So special an Atlas Van Lines 2020 blog asked, "Is Everyone Moving to Maine?"

In fact, a University of New Hampshire study showed that in 2020-2022, Maine had the largest population increase by percentage of any New England state, according to Maine Monitor.

While numbers provide data across the state, we asked local realtors and town officials what they are seeing.

On Southport, fire chief and selectboard chair Gerry Gamage told The Register most home purchases are "People buying for themselves, not as an investment to rent out."

Jonathan Tindal, designated broker and realtor with Tindal & Callahan Real Estate, told the Register they see people buying to live here year round with many choosing to retire here. For some, he said, that means year round use but others may split their time with Florida.

Clayton Pottle, former owner of Pottle Realty Group and managing broker with William Raveis Real Estate, said about 70% of his sales are to people choosing to live here year round.

"We're seeing more remote workers — it's been huge since 2020," he said. "Huge" might also apply to selling prices. "Between 2020 and 2024 prices have actually doubled in some cases. It's just crazy," he added.

So how are prices affecting property taxes?

Here's where higher home prices affect property taxes: Maine has a revenue-sharing program enacted by the Legislature in 1971 that requires the state to return 5% of all sales and income tax to Maine's 482 cities and towns.

By statute, revenue shared from the state can only be used to lower property taxes, but it isn't distributed equally among towns. In general, the more expensive the property is in a town, the less money the town receives from the state. We asked Robert J. Duplisea Jr., Boothbay Harbor's assessor, how the share of state revenue is calculated.

He explained that the amount of property tax starts with the valuation. Every year, the total value of all property in the town is calculated — including recent selling prices.

That total valuation is divided into the town's needed budget and the result is the mil rate.

As explained by Kate Dufour, director of advocacy and communications for Maine Municipal Association in a phone interview, about 80% of the state's revenue-sharing funds are distributed to all towns based on the mil rate. How much each town gets is based on each community’s full value mil rate multiplied by its population.

Towns with more expensive properties have a higher valuation and usually a lower mil rate than towns with less expensive properties.

The higher the mil rate, the bigger the share of revenue a town will receive. Towns with lower mil rates will receive a smaller share of revenue from the state. The remaining 20% of the revenue shared goes to towns that have a very high mil rate (11.3 and above).

"Other than excise taxes and fees, the only way towns raise revenue is through property taxes. Depending on the need for property taxes to fund all local government services, a community that doesn't have much in valuation may need to raise more," Dufour said, explaining the reason behind receiving additional state revenue.

Dufour pointed out that town officials have limited control because a large portion of the property taxes are required for schools and county government. And then there are increasing home prices.

"With COVID," she said, "nobody expected a market disruption of this magnitude. The pandemic reset the value of homes in our state and because of the market, values are going up."

Fair Share?

Last year, Brunswick indefinitely delayed a controversial revaluation because so many residents would see increased property tax bills, according to a 2023 Times Record article.

"We are the canary in the coal mine," Rep. Dan Ankeles told the Register in a phone interview. "Revaluations are triggering a massive property tax shift to people who can least afford it. People are finding property taxes are not within their ability to pay anymore."

Maine Wire reported in April that a WalletHub study shows Maine has the highest property tax in the U.S.

So property owners in popular tourist locations are funding town services that help to make that location appealing. The visitors in turn contribute a significant amount of sales taxes from restaurants, room rentals and other venues. And because the mil rate for many of these towns is lower, the towns receive less of that tax revenue back from the state.

As an example, it's estimated in 2023, Airbnb and Vrbo rentals in Boothbay Harbor generated $779,236 in occupancy taxes, based on data from Air DNA. Those dollars went into state revenue to be shared with towns to offset property taxes.

In return, Boothbay Harbor received $176,359 as its share of revenue from the state. Based on data from the same source, on Southport the occupancy taxes on rentals paid to the state in 2023 would have been $152,764 for which the town received $24,464 as its revenue share from the state.

Other towns with higher mil rates received the benefit of sales taxes generated here from visitors to the Boothbay area.

And the schools?

By law, 55% of the costs to educate schoolchildren in Maine are paid from state revenue coming from individual and corporate income tax, sales tax and cigarette tax.

Just as with revenue-sharing to towns, the funds are not distributed evenly.

Maine Department of Education (DOE) requires all students have an equal opportunity to achieve results. Known as ESP — essential programs and services — the allocation of state funds to a school system is determined by a formula that includes the number of students, ESP costs and again, a town's valuation and mil rate.

This year, total EPS was $2.66 billion and the share distributed to the schools was $1.42 billion, according to Dufour.

So as explained by the DOE in a 2023 presentation, "... if (an) SAU (School Administrative Unit) has a higher valuation times the current mil rate, (aka: higher ability to pay), the ... formula will provide less funds to them, so it can provide more funds to SAUs that do not have as great an ability to pay for the cost of education using local property taxes."

Duplisea estimated about 80% of the town's budget is from costs the town doesn't control and the largest portion of this is the school.

Towns DOE believes can afford to pay more are designated as "minimum receivers," meaning they can raise needed funds from property taxes and so receive a smaller share of the education funds than other schools. The same presentation explained, "In FY 24, 87 out of 256 SAUs, or 34% are minimum receivers."

For example, for the 2023-24 school year, Boothbay-Boothbay Harbor Community School District (CSD) received $610,681.60 as its total share of revenue from DOE. Calais, with a similar size population, received $6,342,493.08. Boothbay-Boothbay Harbor CSD is a "minimum receiver”; Calais is not.

As documented by DOE, Boothbay-Boothbay Harbor’s combined valuation for 2023-24 was $2,191,100,000; Calais, $198,750,000.

Barring the unforeseen, since Maine is home to the oldest population in the U.S. and Lincoln County has the oldest population in Maine, we might not see the number of students in local schools increase.

A decreasing number of students combined with high valuation means unless we change how state revenue is distributed to schools, towns like those on our peninsula may be locked into ever-decreasing state funds for local schools which in turn, lead to higher property taxes so that most families with school-age children are priced out of the area.

How much stays where the revenue is created...?

Our region hosts hundreds of thousands of visitors between Windjammer Days and Harbor Lights, generating tax dollars for the state. In 2022, Gardens Aglow alone saw 120,000 visitors, according to Spectrum News.

That year, tourist spending in Maine was $8.4 billion with 35% coming from the Midcoast and islands, according to Steve Lyons, director of the Maine Office of Tourism as reported by Island Institute. That's $2.94 billion spent here — most if not all of which produces sales taxes for the state.

Yet, according to Fritz Freudenberger's story in The Register last November, "... 44% of income-earning households on the Boothbay peninsula struggle to afford the cost of living." The story tells of United Way of Maine’s report, "ALICE in Maine: A Study of Financial Hardship."

As explained, it refers to those earning more than the federal poverty level, but not enough to afford the basics where they live. As reported, Boothbay has 51% of households below the threshold, Boothbay Harbor has 45%, 44% in Southport and 35% in Edgecomb.

Three of these towns are currently on the "50 Most Expensive List," and are designated minimum receivers for education funding from the state.

Is this Rep. Ankeles’ “canary in the coal mine"?

Property taxes are paying to maintain the infrastructure and services that support a robust tourist economy here that sends millions of dollars of tax revenue to Augusta each year. In return, we receive a small amount from the state in revenue-sharing and school funding while seeing taxes generated here distributed to other towns to offset their property tax bills.

Is it time to adjust the state's revenue sharing formula to reflect current realities of increasing property taxes in locations that are disproportionately contributing to the revenue? How can the state provide additional relief to property owners in these areas?

Next: A look at ADUs and short-term rental properties.