Shadows and Countershadows: 1830-1848

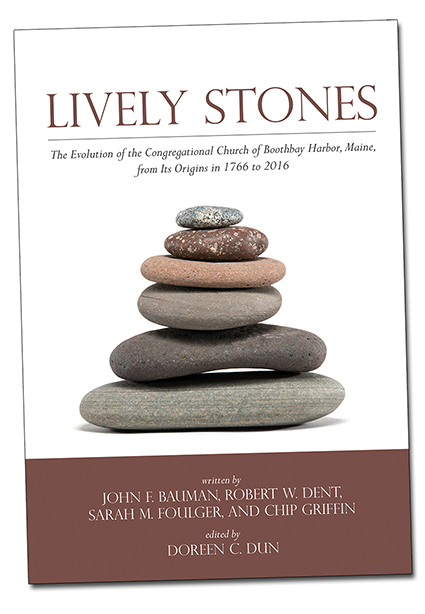

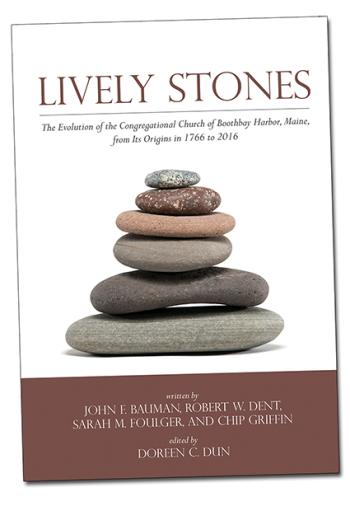

This is the third of twelve monthly articles celebrating our region’s first church 250 years ago, in 1766, and its successor Congregational churches. "Lively Stones: The Evolution of the Congregational Church of Boothbay Harbor, Maine, from its Origins in 1766 to 2016," is hot off the press, co-authored by Chip Griffin, Sarah Foulger, Bob Dent and Jack Bauman.

By Sarah M. Foulger

Between 1830 and 1848, the Second Great Awakening, a religious revival movement, was sweeping the nation, even into somewhat isolated communities like Boothbay. Revivalism not only stirred souls to a closer walk with God but promoted sweeping social change. Popular American revivalist, Charles Grandisson Finney, preached education for women and abolition of slavery. The Congregational Church of Boothbay, drew several revivalist preachers to its pulpit, including the Rev. Charles Cook, a significant and provocative figure in the annals of the church. Leander Coan, who pastored the church from 1865-1867, would write of Cook, “This strange man has gone to his reward.”

Charles Cook was born in Newburyport but his mother, Abigail Davis, was from Boothbay. His maternal grandparents, Hannah Barter and Israel Davis, were both born in Boothbay. His great-grandfather, Israel Davis, was a founder of the original Presbyterian congregation led by Rev. John Murray. It is likely, therefore, that Cook knew Boothbay well and was familiar with the congregation which, unable to secure another Presbyterian minister, had, in 1798, become a Congregational church. It is also likely that, growing up in Newburyport, he had heard stories of the great John Murray, who left Boothbay to serve a congregation in Newburyport.

Cook was called to serve the Congregational Church of Boothbay in 1830. It was reported in the Wiscasset Citizen, “An unusual degree of unanimity has prevailed in the church and parish – the church were unanimous in their call. A reformation has already commenced under his preaching.” According to legal records, Cook was “considered one of the most popular preachers in Maine.” He was a strong proponent of the temperance movement and, somewhat miraculously, convinced the church membership to forsake alcohol, though commitment to sobriety would not endure). Cook also supported the American Colonization Society, raising awareness and funds to free slaves.

By church growth standards, Cook had a notably successful ministry in Boothbay, leading a spiritual revival that increased membership and baptisms. Two years into his ministry, however, Cook asked to leave the church. He was accused of Onanism, detailed as gross and abominable lewdness with young men. The accusation of Onanism refers to the biblical figure, Onan (Genesis 38), who refused to be intimate with his brother’s widow (his responsibility according to ancient Jewish law). All evidence points to Charles Cook being homosexual and, indeed, Onanism was a term commonly applied to homosexuality in the 19th century. The year Cook arrived in Boothbay, he married a young woman named Sophia Horton, but the marriage was unhappy from the start. The transcript of an 1835 Boston trial, where Cook was then living with his partner, Benjamin Baxter, documents Cook’s claim that, at his mother’s insistence, he had mistakenly married.

Prior to his ministry in Boothbay, Cook served a Baptist church in Hanson, Massachusetts. From Boothbay, he served a Unitarian Church in Watertown and may also have served a Methodist congregation. However, no 19th century church would abide a gay pastor. Cook left the ministry, becoming an apothecary in Boston with Baxter at his side. Baxter was soon accused of theft, and Cook, of receiving stolen goods. The aforementioned trial claims to be about these charges but the clear focus of the trial was Cook’s homosexuality. Both Baxter and Cook were sent to prisons. State records indicate that Cook died of consumption in 1841.

Cook’s sexuality created deep anguish within the congregation. David Stinson, in his brief 1998 history of the church, stated that Cook’s ministry contributed to the formation of the Congregational church in Boothbay Harbor and to the demise of the Congregational church in Boothbay Center. The pain, confusion, and division left in the wake of Cook’s ministry was undoubtedly exacerbated by instructions from the Maine Conference of Congregational Churches to “bury” what had happened. However, had Cook not departed Boothbay under the shadow of what was at the time scandalous, he would long be remembered for his enthusiastic revivals, lively sermons, ability to draw members to the church, and fervent commitment to ending slavery and addiction to alcohol.

In 1844, the Rev. William Tobey, a noted abolitionist, took the pulpit in Boothbay. In 1839, the year of the ship Amistad’s capture in Connecticut, Tobey had delivered an impassioned address, preaching, “What can be more benevolent than to restore the oppressed sons of Africa to the land from which they have been torn by cupidity and lawless violence? What more proper or more just than to seek to repair as far as practicable the wrong that has been done…?” Based on its choice of pro-abolition pastors and ongoing support for the anti-slavery American Missionary Society, it is fair to suggest that sermons condemning slavery were preached regularly from the pulpit and that the Congregational church then, as now, was a place in which justice and equality were sought.

Event Date

Address

United States