Historic vessel ‘Bowdoin’ to visit Rockland in honor of captain who kept her afloat

A replica of the schooner Bowdoin resides among artifacts donated to Jim Sharp’s Sail, Power and Steam Museum by Admiral Donald MacMillan. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

A replica of the schooner Bowdoin resides among artifacts donated to Jim Sharp’s Sail, Power and Steam Museum by Admiral Donald MacMillan. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

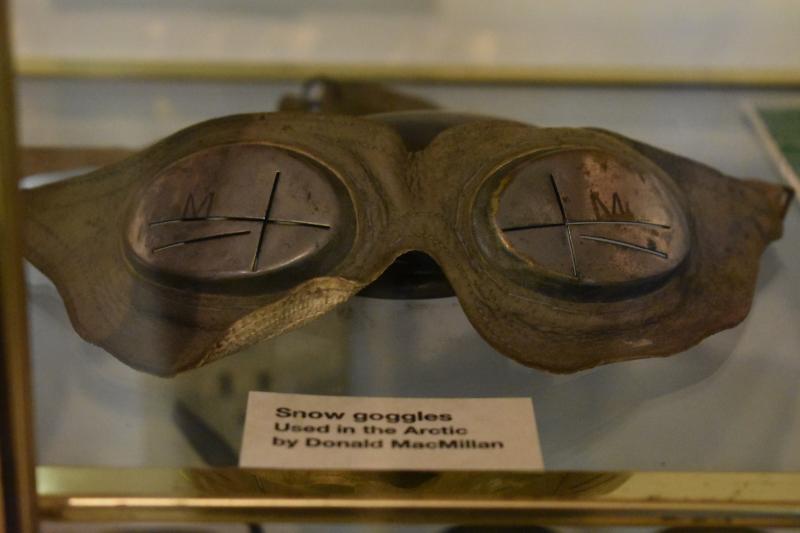

Goggles to protect the eyes. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Goggles to protect the eyes. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Binoculars. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Binoculars. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

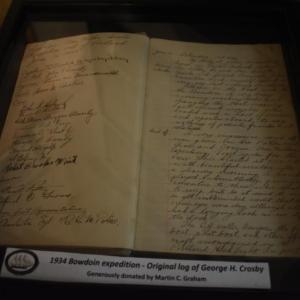

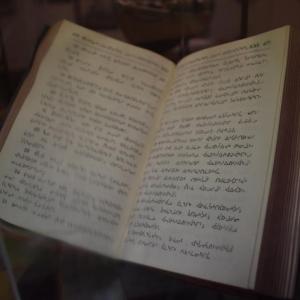

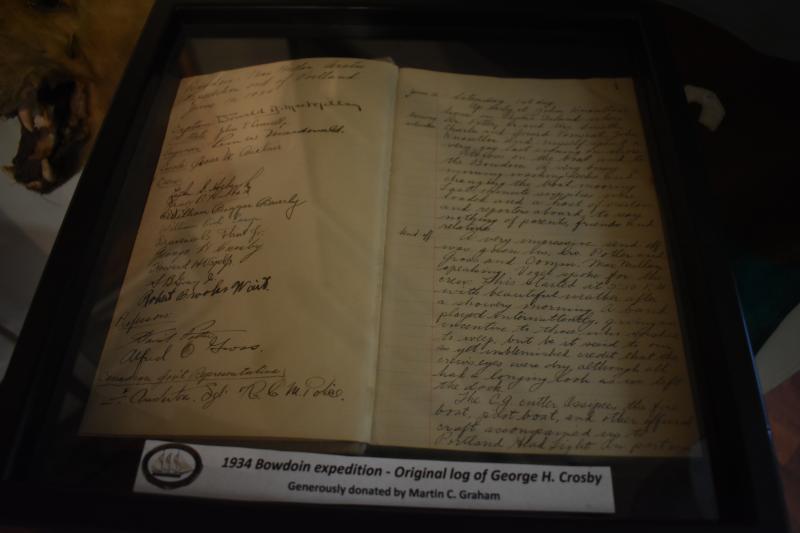

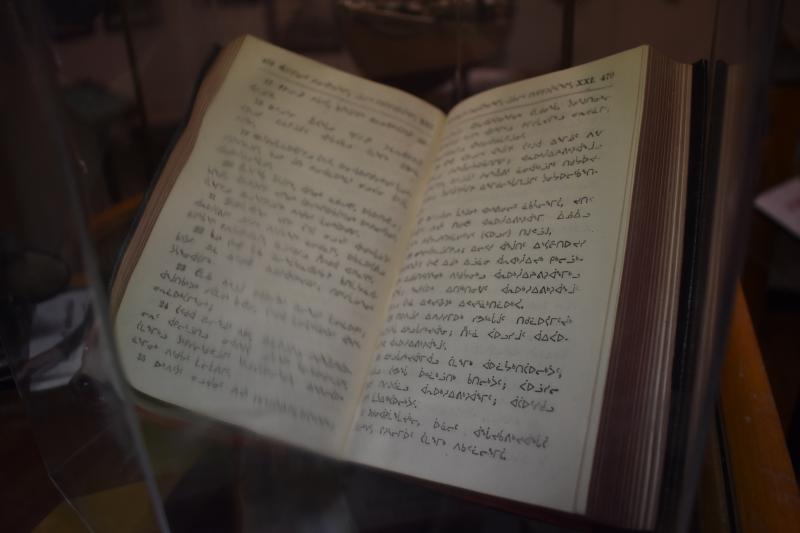

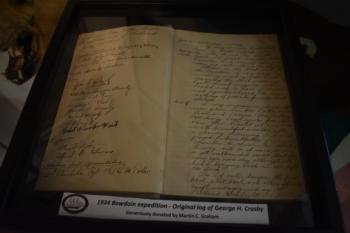

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

The ball from the original masthead. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

The ball from the original masthead. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Clothing made by Eskimo natives. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Clothing made by Eskimo natives. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

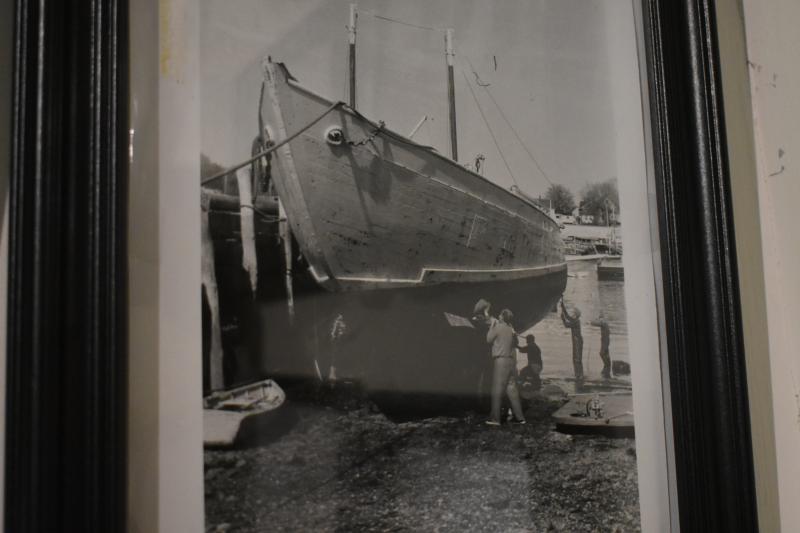

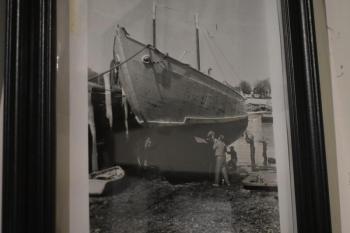

The Bowdoin as it was when Sharp pulled it to Camden circa 1967. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

The Bowdoin as it was when Sharp pulled it to Camden circa 1967. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

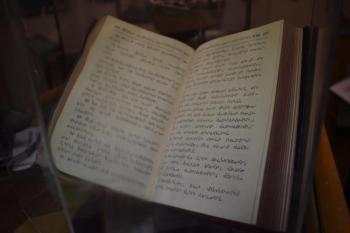

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

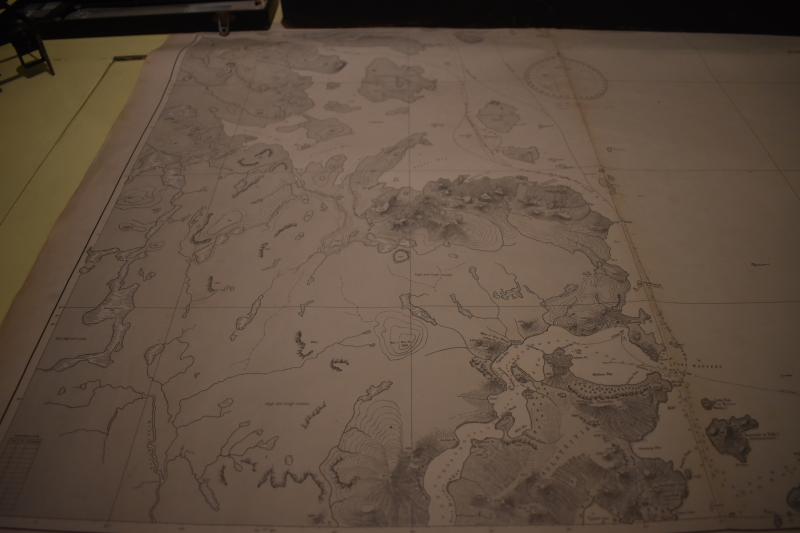

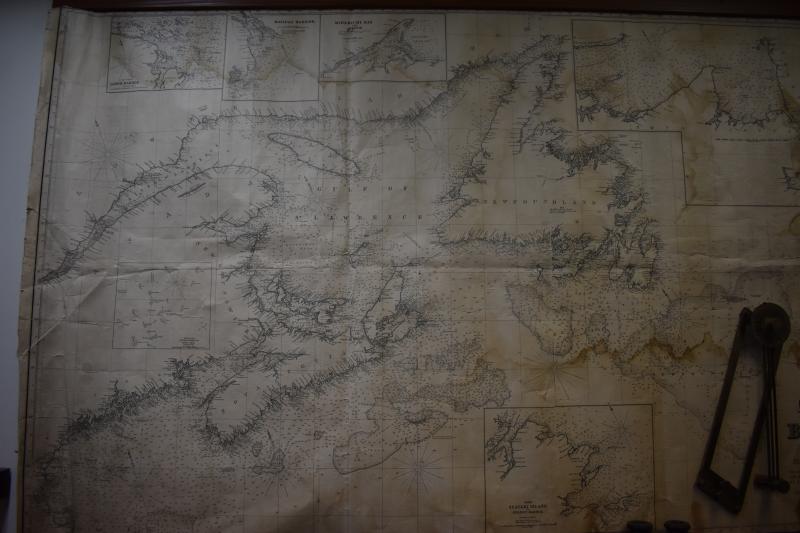

MacMillan’s map of the Arctic. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

MacMillan’s map of the Arctic. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Admiral Donald MacMillan.

Admiral Donald MacMillan.

A replica of the schooner Bowdoin resides among artifacts donated to Jim Sharp’s Sail, Power and Steam Museum by Admiral Donald MacMillan. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

A replica of the schooner Bowdoin resides among artifacts donated to Jim Sharp’s Sail, Power and Steam Museum by Admiral Donald MacMillan. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Goggles to protect the eyes. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Goggles to protect the eyes. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Binoculars. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Binoculars. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

The ball from the original masthead. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

The ball from the original masthead. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Clothing made by Eskimo natives. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Clothing made by Eskimo natives. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

The Bowdoin as it was when Sharp pulled it to Camden circa 1967. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

The Bowdoin as it was when Sharp pulled it to Camden circa 1967. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

MacMillan’s map of the Arctic. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

MacMillan’s map of the Arctic. (Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

(Photo by Sarah Thompson)

Admiral Donald MacMillan.

Admiral Donald MacMillan.

ROCKLAND — Forty eight years ago, Capt. Jim Sharp steered a restored vessel along the shores of Provincetown, Massachusetts, so that her original captain could take a final glimpse of his claim to fame. The tables have now turned, with Sharp being the one to stand ashore and watch as the historic research ship he’d help to save from derelict heads to Rockland, restored again, and preparing for its 100th anniversary return trip to the Arctic in 2021.

Next weekend, September 28, the vessel’s current owner, Maine Maritime Academy, will pilot the schooner Bowdoin into Rockland Harbor in honor of Sharp.

In 1971, as Sharp and his crew inched the vessel toward the shoreline home of Admiral Donald MacMillan, an estimated 400 spectators gathered along the banks for their own glimpse. But, there was a problem. Thick fog greatly reduced visibility.

For hours, Bowdoin inched forward, its passengers filled with nerves that the ailing 96-year-old admiral who’d named the vessel after his alma mater, who’d traveled with Robert Peary to the North Pole, who’d been a part of creating the first written bible for the Arctic Eskimos, would not see his ship afloat again.

She edged closer and closer, until she was almost in front of the home, according to Sharp. And then, as dramatic a tale as the time MacMillan’s crew spent an extra several months trapped in the Arctic ice following a year-long expedition, the fog suddenly lifted. There on shore stood MacMillan, watching his vessel approach. Two hundred/three hundred feet later, they re-entered the fog bank.

The crew waved and MacMillan fired a cannon salute as Bowdoin tied up at the dock, “and 400 people tried to come down, come aboard,” said Sharp.

MacMillan died seven months later.

Now, it’s Sharp’s turn to watch Bowdoin sail again, this time, under the guidance of MMA’s captain, Will McLean.

“I had this wild idea when I heard that the Bowdoin was down in Boothbay getting totally reworked,” said Sail, Power and Steam Museum board member and former Smithsonian project manager Barbara Mogel.

“I knew they had to bring the boat up at some point from Boothbay,” she said. “So I was thinking, wouldn’t it be great if we turned the tables on Jim and had the Bowdoin come sail by Rockland, for him to see?”

For more than six months, the vessel has sat in dry dock at Bristol Marine, in Boothbay, undergoing hull restoration in the town that launched her 102 years ago. By mid-December, 2018, multiple planks had been identified for replacement.

“We’re removing the 18 planks, but you don’t know what we’ll find until they come off,” Project Manager Ross Branch told Boothbay Register reporter Bill Pearson in December.

With the restoration completed, Mogel had asked that the ship complete the honorary sail-by on her way back to Castine. In turn, MMA convinced her to wait until the rigging, which was left at the Academy, was reestablished.

Not that Sharp hasn’t seen Bowdoin without rigging. In fact, that’s how he found her during his 1967 trip to Mystic Seaport Museum, where she’d been initially promised a safe haven.

According to Sharp, his friend MacMillan retired, outfitted his ship as if he were going to Greenland again. MacMillan added his sails, brought his navigational gear on board, and donated the vessel to Mystic Seaport.

“They never lifted a finger for her maintenance,” said Sharp. “They never put any oil for her decks. Never put any paint on her. She lay there through the ravages of weather over and over again, winter and summer without any cover.”

After a visitor came aboard and stepped down through a floor-deck plank, the Bowdoin was closed to visitation.

They then took the masts out, they broke the main sail and the main mast, then stripped her – including the engine, which was cut out of the hull.

They were going to sink her hull and sell everything aboard worth selling.

So Sharp and his friend Ransom Kelly, from Boothbay, put the spars and the engine (which was lying in the sand) into the Bowdoin and used Kelly’s party boat to tow her to Camden.

Since then, Bowdoin has helped teach young sailors about the ocean, and has returned to the Arctic at least once.

She will do so again, when she turns 100.

A story only Capt. Jim Sharp could tell

Admiral Donald MacMillan spent four years living with the Eskimos, learning their culture.

“Eating and breathing and exercising and doing what the Inuit do,” said Sharp.

In the teens (the 1910s, that is), he wanted to build a research vessel to go North. The result is the Schooner Bowdoin.

Built scientifically. Built on what they call dead rise from the water line down. She was wedge shaped, so if she got nipped in the ice, she wouldn’t crush. She would pop up, courtesy of design features added by Bristol Marine, in Boothbay.

A whole team went north in the vessel, a group of scientists: botonists. biologists, geologists, 18 of them.

He went way up north, as far north as you could get on the northern end of Greenland without going on the polar ice cap.

They went into a little place called Refuge Harbor. Well protected. A little, small entrance. And they plopped their anchor down in the middle of the summer. And there they sat for 335 days doing scientific work all through the dark winter. They were prepared for that. That’s what they were there for.

They banked up snow all around the vessel to keep warm. They built igloos – 3 igloos on deck so that they could get in and out – not only for protection of the vessel but for protection from polar bears. Polar bears wouldn’t come into the igloo and go down into the vessel, even though they were cooking down there. And of course, that attracts polar bears.

They were there all winter long. And, come spring, they had to get back to Gloucester, so come summer, everything was fine, except that the ice hadn’t melted. Come September, they were getting fresh ice.

How to get out?

They had a coal stove down in the bowels of her. And they decided that they would take that coal and they would put it ahead of the vessel on the ice. Put the soot there. The darkness attracts the sun and breaks the ice. Makes it weak.

So they had an old seal engine in her, backed her up, smashed into the ice and break it up; put more coal out, did that again, and again and again, until they finally worked their way over to that little feather of waterway around the shore that kept open by the tides going up and down ten feet.

Of course, at low time, it’s all a beach, a boulder-laden beach. At high time is the only time they could ever move. So they had to wait for the very top of the tide, then they’d only have about an hour at the very most to move, and then they’d be banging on rocks, banging against the ice.

But then a fresh iceberg moved in, closing off the entrance to the inlet. But it had a neck of ice that was sticking out and caught on a rock. Without hitting the rock, without hitting the ice berg, they could smash against that little neck of ice. They might be able to slide out through just before the wind would blow and shut off the whole harbor again.

So they backed up the Bowdoin all the way up as far as they could go on the top of the tide, nailed down the govern, and went a-hell-and-be-larabee into the bank, and slid right up, and slid right back again. Couldn’t get out.

What to do? They were only prepared for one winter. Had to get out somehow.

Only thing to do? Try again. But they needed a higher tide. A higher Rogue tide so they could get more fetch. Get back further. More inertia. So they had to wait several days for the tide.

They backed up much further, so they could get all of the inertia they could get. They came and slammed into that piece, and they slid out through just as that iceberg blew in and shut it off all over again.

But that was only the beginning.

Back they went to the Arctic, over and over again, 25 more times.

They wintered in at the northern part of Labrador. Wintered in on part of Greenland. They had no charts. They had no way of knowing where the rocks were. And being nipped in the ice, and all of the vicissitudes that a research vessel goes through – what the Bowdoin went through over and over again.

Event Date

Address

United States