Becoming Congregational and Losing Control 1798 – 1830

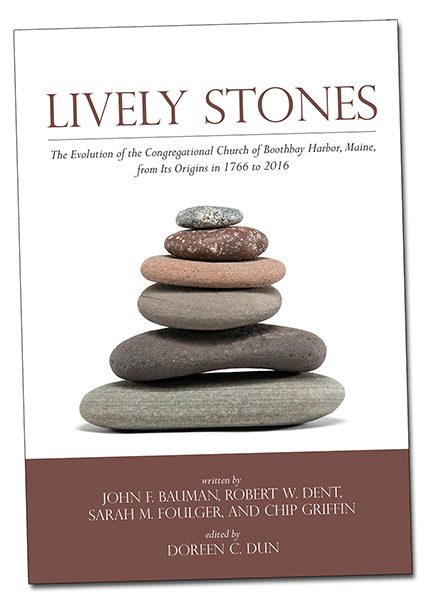

This is the third of twelve monthly articles celebrating our region’s first church from 1766 to 2016. “Lively Stones” is hot off the press, co-authored by Chip Griffin, Sarah Foulger, Bob Dent, and Jack Bauman. “Lively Stones” is the first history book of our Boothbay Region community from its founding, in over a century.

By Chip Griffin

Our last two articles summarized Scots-Irish Presbyterian settlement here from 1729 to 1798 and highlighted Reverend John Murray, the town’s first settled minister, who led Boothbay’s church from 1766 to 1779, sparked the first great spiritual revival in Maine, and represented Boothbay during the American Revolution.

Boothbay’s fledgling Congregational Church inherited the 1766 Presbyterian Church building at the north end of the larger Boothbay Common, north of the present Civil War monument. Congregationalism was blessed with three successive and successful ministers, each of whom served between seven and thirteen years. They and their families lived next to the church in the 1796 parsonage, last used as the Center Café just south of today’s Common.

In 1797, remaining Presbyterians called Reverend John Sawyer as their minister, but a year later Presbyterians requested assistance from the Lincoln Association, a Congregational association extant today. These Presbyterians created, on September 20, 1798, the new Boothbay Congregational Church and adopted the Congregational Articles of Faith and Covenant that declared: “We will make it our business as far as in us lies, to build up of lively, and only lively stones [emphasis added], a spiritual-house, growing into an holy temple in the Lord.” The Covenant’s “lively stones,” the name of this new book, was a biblical reference to 1 Peter 2:5. The 1798 Covenant concluded: “[A]lso, to abstain from all profaneness, chambering [i.e., adultery or fornication], and wantonness – pesting, tattling, and backbiting – and all practices which do not tend to promote godliness.” That was the ideal, too often broken.

This nascent church prospered due to Maine Congregational support, increased local population, and rising tides of trade and manufacturing between 1798 and 1830. The Second Great Awakening of the 1790s barely touched Boothbay’s Presbyterians and Congregationalists, but fired up area Methodists and especially Baptists. These competing churches vied for Congregationalists following the Puritan/Congregational stranglehold on church and state from 1630 until around 1800. Maine separated church and state in 1834.

Sawyer tried but failed to empower Boothbay’s church women during his Congregational tenure from 1798 to 1805. Church men praised church women for cleaning church linens, but rejected Sawyer’s advocacy and prohibited women from church decision-making. Although women formed a majority throughout Boothbay’s church history, church men during this period marginalized, charged, tried, and convicted church women disproportionately more than men for the leading Congregational Church crimes of intoxication, fornication, and adultery.

Reverend Jabez Pond Fisher served Boothbay from 1807 to 1816. Jabez Fisher married local Fannie Auld two years into his Boothbay tenure, they raised their young children in Boothbay until Fisher asked to leave near the end of 1816, and he was remembered as intelligent but eccentric. Fisher’s tenure endured the hugely unpopular Mr. Madison’s War, the War of 1812.

Reverend Isaac Weston served from 1817 to 1830, then second only to Murray in stature and tenure. Weston grew the congregation and baptized an incredible 38 children in July of 1818. In 1856, Weston commemorated the Boothbay church’s 90th year celebration and decried excessive liquor consumption in Boothbay and its church. Alcohol has been a serious problem for Boothbay, identified by many pastors before and since Weston, amply documented in church session cases for both Presbyterians and Congregationalists, and detailed in Lively Stones.

Boothbay Baptists were mostly farmers and workers, Jeffersonian politically, and concentrated in Back River and north of the Center, while Methodists first gathered in Southport and later in Boothbay Harbor and East Boothbay. Boothbay Congregationalists were generally more prosperous maritime merchants and town leaders, more Federalist politically, and more centered in the Harbor, where they often met at places like the Fullerton home, where the Boothbay Harbor Post Office is today. This growing social, political, economic, and geographic gulf, dividing Congregationalists from Baptists and Methodists, rapidly occurred between 1798 and 1830. This divide presaged and harbored a formal split of the town over water, fire insurance, and tourism six decades later, in 1889.

Like the legendary John Murray’s extraordinary Boothbay ministry, Isaac Weston’s astounding success in Boothbay was followed by dismal failures in church and pastoral leadership. This 1830 failure will be glimpsed through the incredible story of the Reverend Charles L. Cook, brilliantly and deftly unearthed, assembled, and narrated by our remarkable Dr. Rev. Sarah Foulger, in Chapter 5 of “Lively Stones.” Sarah’s narrative, to be summarized by her in April, informs and haunts us three centuries later.

Event Date

Address

United States