The final Café Scientifique: What lies ahead

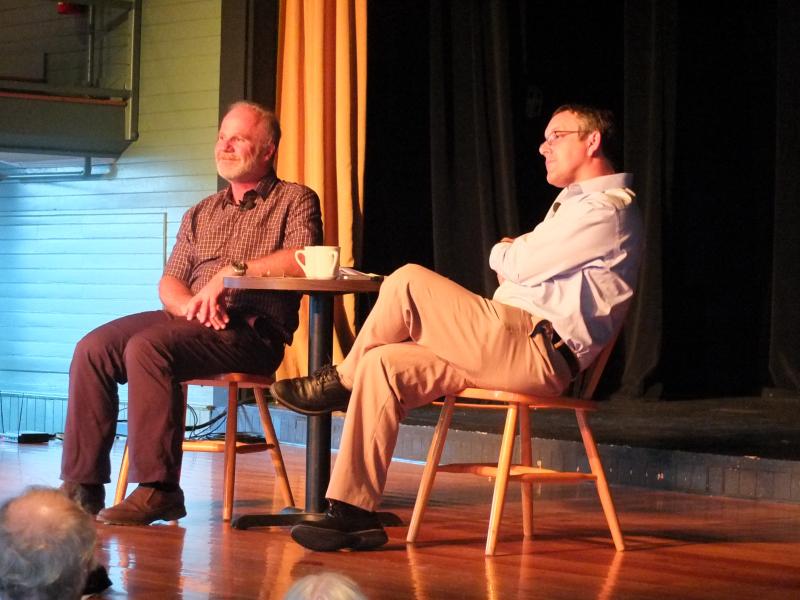

Dr. Graham Shimmield, left, and Colin Woodard speak to audience members Aug. 19 at the Boothbay Harbor Opera House during the final Café Scientifique of the season. CASEY HOUSER/Boothbay Register

Dr. Graham Shimmield, left, and Colin Woodard speak to audience members Aug. 19 at the Boothbay Harbor Opera House during the final Café Scientifique of the season. CASEY HOUSER/Boothbay Register

Dr. Graham Shimmield, left, and Colin Woodard speak to audience members Aug. 19 at the Boothbay Harbor Opera House during the final Café Scientifique of the season. CASEY HOUSER/Boothbay Register

Dr. Graham Shimmield, left, and Colin Woodard speak to audience members Aug. 19 at the Boothbay Harbor Opera House during the final Café Scientifique of the season. CASEY HOUSER/Boothbay Register

To move forward, they first had to travel backward.

This past Tuesday, in front of a crowd that filled the Boothbay Harbor Opera House to near capacity, Colin Woodard and Dr. Graham Shimmield discussed the future of oceanography and science as we know it.

At the final Bigelow Labs Café Scientifique, “40 Years of Discovery and What Lies Ahead,” the pair first began with their respective histories and told the audience where they stood 40 years ago.

Woodard, now a national affairs writer for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, was just a child four decades past. He said he grew up in Southport, and in those days, when he was five years old, he would sail with his family on small sailboats for days at a time.

"To be tied to the wind and the currents, you begin communing with nature," Woodard said. "It comes to seem more real than anything else."

This was the beginning of his immersion of the sea, and he said it set the stage for his interest in oceanography later on in life.

Shimmield, now the executive director of the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, was a few years older than Woodard at that time, but said he also grew up near the water. His parents lived in Trinidad and had a home that sat right on the beach. He had ample access to the ocean.

"By living in a place like that and being so close to the sea," he said, "I found the sea, beach and marine life totally fascinating.

"I remember a profusion of coral and marine life. I had always wanted to go to sleep, falling asleep, to the sound of the sea."

Woodard then described his reporting on environmental problems in the ‘90s in Europe. He lived in Budapest near the Danube River, and he spoke about how the Danube became the central image of pollution for him. He said he was one of the first to ask the ultimate hard question about where the pollution was heading. It went directly to the Black Sea.

"It was a biochemical disaster that no one saw coming," he said.

Pollution caused algae blooms that suffocated other life in the sea. And eventually an influx of jellyfish made the problem even worse by populating the area with no natural predators. Jellies grew to over 10 billion tons in total mass at one point.

"Have we reached a point where we can disrupt entire collections of species?" Woodard asked. First it was his experience of the ocean; then his first-hand witnessing of destructive pollution that thrust him into focusing more on similar issues.

Shimmield said his eventual entrance into the field of oceanography was more accidental. He worked on oil rigs around the time that he went to college, and he was able to see the impact the rigs had on different parts of the ocean. He was isolated and away from any other man-made structures, and that isolation brought things into focus for him.

They each agreed that their experiences made them realize that ocean life, indeed all life, was connected and that it was not right to think of different parts of the ecosystem as acting completely independently. That realization across all science has led to the development of ecosystem-based management, an approach to environmental management that considers all issues simultaneously rather than focusing on each issue in isolation.

The pair's history lead directly into questions from the audience. Since this night was meant to be more of a question-and-answer session more than the previous Bigelow talks, audience members were given about 20 minutes to converse with the presenters.

One audience member asked about the pervasive issue of spreading the message of science. "How do you get your message out?"

Shimmield said he believes that communication begins with advocacy for the oceanic sciences, which then leads to large-scale perception.

"Scientists are going through a period where they need to be counted and find out what they actually believe," Shimmield said. "That's a zone of discomfort for most scientists."

Instead of simply completing research in labs, he said, scientists must stand up for themselves and their professions by connecting with others through direct messages. They may be able to create advocates from those messages, and their efforts with a few individuals can blossom into widespread perception that, for instance, Earth systems rely on, and can affect, each other, so the actions of humans have a definite impact on the rest of the planet.

Regarding a related issue, a separate audience member brought up the Republican senator from Oklahoma, Jim Inhofe, who has spoken out directly against climate change science. The event participant asked Woodard what could be done about people, especially prominent public figures, speaking out against scientific evidence.

He responded simply by saying that getting the facts out will not always solve the problem. "People will ignore the facts," Woodard said.

The last question came from a man who described a photo of the Earth that was taken from space. The photo, an heirloom in his own family, shows a blue planet, and that amount of blue, he said, suggests that the oceans are clearly important because of their prominence on the planet. That said, he asked Shimmield how the scientific community was prepared to tackle such a physically large element with the funding they receive either privately or through government entities.

"I am concerned as a director of the (Bigelow) lab and for my colleagues," Shimmield said. Funding is harder than ever to get, he said, and at the same time, the cost of science is rising.

He quoted a recent figure and explained that 60 percent of scientific funding goes toward infrastructure: "That's just to keep the machines running."

He advocated for scientists being deliberate about their funding needs, and he stressed that it was important to get across the message that scientists only ask for money from governments after they have sat down and thought about it for long stretches of time. They are not asking for funds based on a whim.

The pair concluded the evening by remarking that that ocean has proven itself as resilient. The Black Sea, Colin said, has recovered after people began to clean up the Danube and lessen the pollution.

"When the pressure is taken off, ecosystems do rebuild."

Event Date

Address

United States