A Dramatic Behind-the-Scenes Story of the Return of Bald Eagles

Fifty years ago, there were fewer than forty nesting pairs of bald eagles in Maine. Today, there are more than 700. Courtesy of Allison Wells

Fifty years ago, there were fewer than forty nesting pairs of bald eagles in Maine. Today, there are more than 700. Courtesy of Allison Wells

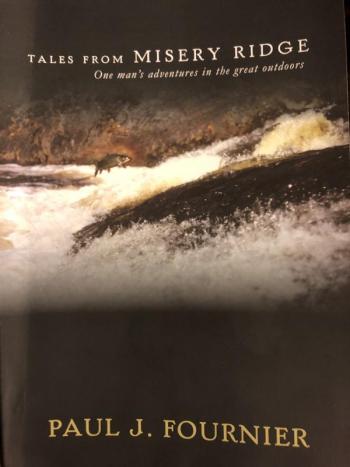

Paul Fournier’s book includes great stories of adventures in the Maine outdoors, including a riveting tale of the transplant of bald eagle eggs as part of the species’ recovery during DDT era.

Paul Fournier’s book includes great stories of adventures in the Maine outdoors, including a riveting tale of the transplant of bald eagle eggs as part of the species’ recovery during DDT era.

Fifty years ago, there were fewer than forty nesting pairs of bald eagles in Maine. Today, there are more than 700. Courtesy of Allison Wells

Fifty years ago, there were fewer than forty nesting pairs of bald eagles in Maine. Today, there are more than 700. Courtesy of Allison Wells

Paul Fournier’s book includes great stories of adventures in the Maine outdoors, including a riveting tale of the transplant of bald eagle eggs as part of the species’ recovery during DDT era.

Paul Fournier’s book includes great stories of adventures in the Maine outdoors, including a riveting tale of the transplant of bald eagle eggs as part of the species’ recovery during DDT era.

Conservation success stories are always cause for grand celebration. Here in Maine, we think of the return of wild turkeys, the restoration of Atlantic puffins and other seabirds, and, of course, the amazing rebound of the bald eagle. Despite it being our national bird and symbolic in so may ways, the bald eagle was truly on the ropes by the 1960s. The impact of DDT and other factors had reduced Maine’s population to fewer than 40 nesting pairs by the 1960s and 70s. Through a dedicated decades-long series of efforts and changes, that number is now well over 700 pairs, and sightings of eagle have become a daily occurrence across the state.

That summary is all well and good, but the truth is, getting to that astonishing turn-around for bald eagles took vastly difficult and involved conservation and policy work. Often the nitty-gritty details are known to only a few people and may eventually be lost to history.

That’s why we were delighted to stumble across one of the behind-the-scenes stories of what it took to bring bald eagles back to the state in a new-to-us book by the late Paul Fournier called “Tales from Misery Ridge” (Islandport Press 2011). Paul had a long history of Maine outdoor activities and pursuits, including a 20-year stint as the public information officer for the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife.

It was during that time that Paul was tasked with documenting the first-ever project attempting to bolster Maine’s struggling bald eagle population by bringing in foster eggs (and then later foster nestlings) from a healthier eagle population in another state. Paul recounts how in 1974 a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist recruited an accomplished tree-climber and grad student to climb into eagle nests in Minnesota to retrieve eggs to be brought back to Maine. They hoped to retrieve at least six eggs, but after wet and slippery conditions caused the climber to have a scary but not injurious fall from a tree, they settled for three eggs. The eggs then had to be carefully kept warm while the two men flew back east on a commercial flight, and drove up to Maine from Boston where they had landed at Logan Airport.

We were surprised and delighted to discover that the first nest that they had identified in which to place one of the eggs was on an island in the Kennebec River in South Gardiner—there is still a bald eagle nest on this same island today. Many springs, we have zoomed into that nest with our telescope to watch the adult eagle sitting on the nest. We had never known of the significance of the place to early bald eagle recovery!

Back in 1974, when the biologists climbed into the South Gardiner nest, they found a brown, empty egg—a by-product of the DDT accumulation in the bodies of the eagles back then. The eagles hatched the new, foster egg that spring but, sadly, the eaglet disappeared later that year before it could fledge.

The biologists placed the second egg in a nest on Swan Island in Richmond where they also found an unviable egg in the nest. Incredibly, as the climber was getting ready to leave the nest, a tree limb fell from above and cracked the precious egg. They had no choice but to replace it with the last of the three eggs that had accompanied them from Minnesota.

That egg did hatch, and the young bird survived to fledge. In later years the biologists decided to transplant young eagles rather than the more delicate eggs. In addition, the banning of DDT was instrumental in protecting eagles and their nests, bringing eagles back from the brink.

Such details inspired our increased appreciation for the kind of dedication it takes to keep a species from becoming relegated only to history.

The book is also just a great read. We highly recommend it to anyone interested in Maine’s natural history.

Jeffrey V. Wells, Ph.D., is a Fellow of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Vice President of Boreal Conservation for National Audubon. Dr. Wells is one of the nation's leading bird experts and conservation biologists and author of the “Birder’s Conservation Handbook.” His grandfather, the late John Chase, was a columnist for the Boothbay Register for many years. Allison Childs Wells, formerly of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is a senior director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, a nonprofit membership organization working statewide to protect the nature of Maine. Both are widely published natural history writers and are the authors of the popular books, “Maine’s Favorite Birds” (Tilbury House) and “Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao: A Site and Field Guide,” (Cornell University Press).

Event Date

Address

United States