Ubiquitous Late-Summer Goldfinches

Around this time of year, late-summer, fifteen summers ago, we went on a road trip to watch a nephew play on the Maine team for the New England regional championships of the Little League World Series in Connecticut. We were fascinated to discover that at every rest area, gas station, convenience store, restaurant, or other place that we stopped along the way — and, yes, at the baseball stadium as well — the bird species that we found at almost every location was not the crow, robin, or house sparrow. It was the American goldfinch.

Since that time, we have continued to observe the same surprisingly ubiquitous distribution of these colorful finches in our late-summer travels in Maine and other parts of the northeastern U.S. (including a recent road trip to upstate New York). It’s not that we see a lot of them in any one location. More often than not, at any spot, we hear just one or two giving their high, querulous calls or their familiar “potato-chip” notes as they fly overhead.

But they seem to be almost everywhere.

Part of that is probably because, unlike most birds, American goldfinches nest in the late summer instead of the early summer as most songbirds do. Two potential reasons have been suggested for this late-summer breeding behavior. One is that, unlike other finches, American goldfinches molt in the spring. Many of you who feed goldfinches through the winter can attest to this fact as you will have watched birds, especially the brightly colored males, show patches of bright yellow as the new feathers come in through the late winter and spring.

Growing new feathers in the spring, though, carries an energetic cost as the body has to assimilate the proteins necessary for feather growth. Goldfinches are exclusively seed eaters, and it is harder to get lots of protein from seeds as compared to birds that eat insects or meat. Consequently it might be physiologically challenging for a bird to move into mating and nesting when it has recently gone through the process of growing a new suit of feathers.

Another explanation (and one that could work together with the first one) is that goldfinches delay their nesting to ensure that their young are hatched when seeds are more abundant. Insect-eating birds have evolved to time their peak reproduction to when there are lots of insects to feed the young, which means that they nest in our area from late May through early July. Warblers are a prime example.

But not only do adult goldfinches eat only seeds, they are unusual in that they feed only seeds to the nestlings. They must have to feed them a lot of seeds, too, since the chicks require a huge input of protein (relative to their size) as they grow their bones and muscles and other protein-based tissues. Seeds, of course, are the reproductive output of those beautiful spring and early-summer flowers that we all enjoy. The seeds ripen in the late summer, and that’s when goldfinches nest.

An interesting side story concerns brown-headed cowbirds, which you may remember are nest parasites, the females laying their eggs in other birds nests to trick the host into raising them. Brown-headed cowbirds fairly regularly lay their eggs in goldfinch nests. But because young cowbirds need lots of insect protein, they usually cannot survive in a goldfinch nest for more than three days. Cowbirds can never successfully parasitize American goldfinches, so for them, the lure of the nest is a dead-end.

Jeffrey V. Wells, Ph.D., is a Fellow of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Dr. Wells is one of the nation's leading bird experts and conservation biologists and author of the “Birder’s Conservation Handbook.” His grandfather, the late John Chase, was a columnist for the Boothbay Register for many years. Allison Childs Wells, formerly of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is a senior director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, a nonprofit membership organization working statewide to protect the nature of Maine. Both are widely published natural history writers and are the authors of the popular book, “Maine’s Favorite Birds” (Tilbury House) and the newly released “Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao” from Cornell University Press.

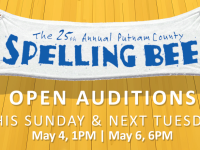

Event Date

Address

United States