‘Tourism, the Great Depression, and the Saga of the Southport, Maine, Thru-Truss, Swing Bridge, 1870-1980.’

To paraphrase an oft-quoted 1818 peroration by Daniel Webster (about Dartmouth College) “It is a small bridge, but there are those of us who love it.” Southport Island to the Boothbay Harbor mainland (Maine Bridge 2789), reflects not only the growing importance of tourism in the late 19th century Boothbay Region, and- as well - the eclipse of Mid-Coast Maine’s maritime past, but also, to the importance of the Federal Government in funding transportation infrastructure in the 20th century.i

Both a seafaring and a shipbuilding people, Southporters’ tie to the Boothbay mainland in the 19th century rested as much on the island’s Scots-Irish- Calvinistic heritage as it did on its maritime heritage. Indeed, with its mid-19th century fleet of 59 fishing vessels regularly harvesting cod on the “Grand Banks.” Southport potentially rivaled places like Gloucester, Massachusetts as an eminent New England fishery.

However, after the Civil War Southport’s once teeming cod and mackerel fishery faced decline and its seafarers diversified by adding to their once cod and mackerel-based economy lobsters, but also fish oil. However, a new, and more important industry arose, one that simultaneously tightened the link between the island and its mainland: namely the enterprise of hosting summer visitors. Summer cottages had long appeared on Boothbay Harbor’s Squirrel Island; indeed, as early as 1788. Meanwhile, on Southport, Bay View House – overlooking Capital Island – opened in 1876, and by 1880 clusters or colonies of “summer cottages” dotted Dogfish Head and other places on the island, all accessible by steamship or ferry.

Soon summer hotels/resorts, and guest or boarding-houses attracted visitors to Southport Island, including Bay View House, the Old Homestead Cove Cottage, the Lawnmeer Inn, and Cozy Harbor House. This brisk new Southport industry, i.e., tending to summer folk, functioned not only to considerably enlarge Southport’s seasonal population, but also to greatly enhance the island’s need for an improved, more reliable means of conveyance to and from the mainland. ii

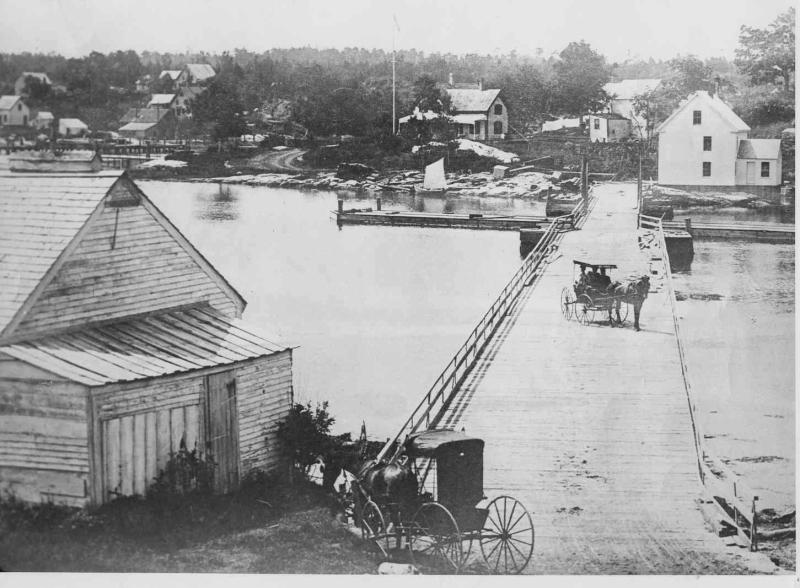

In the 1860s a wooden toll bridge had been built from Oak Point on the Boothbay Harbor side of the Gut to a site on Southport near what is now the Ocean Gate Motel. In 1871 nor’easter winds demolished that wooden toll bridge. From 1871 to However1876 a “private” ferry replaced it. The ferry service endured until 1896 at which time the Town of Southport voted to spend town money to build a new wooden toll bridge at the Thompson or Decker’s Cove site. iii

In his monumental 1906 History of Boothbay, Southport, and Boothbay Harbor Francis B. Green stated explicitly that, after over 100 years, the newly 1896-built wooden bridge at last afforded Southporters “the advantages of [the] mainland.” Howeve, although the Southport town meeting approved monies for building the new wooden toll bridge, it did so parsimoniously, limiting the cost of its construction to $6,000, the monies to be funded by a 10-year bond issue. Separately, the town voted $700 to build a toll-keepers house adjoining the bridge, the house described as a two and ¼ story clapboard-frame structure. While the bridge benefitted both towns (Southport and Boothbay Harbor) Southport assumed full responsibility for building and maintaining the span, which included a manually - operated swing section facilitating boat passage. The Harbor paid half the cost of repairing the bridge.

The new wooden toll bridge - operated by the Southport Bridge Company - opened in 1897, thus terminating the ferry service. Pedestrians and bicyclists, the latter a new rage at the time, paid 5 cents to cross; carriages, sleighs and other horse drawn vehicles paid $.20. Nevertheless, while the bridge boosted tourism, cheaply built, the wooden, plank-surfaced bridge, with its tenuously attached board railings, barely – if at all - escaped the charge of being “rickety.”

Beginning in 1914 lobbying commenced to have the wobbly bridge replaced with a steel toll-free structure. Rebuilt 1916 , the wooden toll bridge appeared more substantial, sadly, it lacked the panache, sturdiness and durability of a more desirable steel structure. By the 1930s, when Southport now sent island high school students to the Boothbay Region High School, the town’s school-bus driver, together with its growing number of “motorists,” no longer trusted the bridge to safely bear much weight, especially a bus crammed with students. At the bridge entrance, students were forced to disembark; the bus then crossed the aching, groaning bridge while the students followed behind trudging across on foot. iv

From a Town-Owned to a State Bridge

However, in the early 1930s these burdened Southport high school students hardly trudged alone. The Great Depression, its onset marked by the New York stock market crash of October 1929, struck the nation, but also impacted the Boothbay Region. Unlike urban America, the Region never witnessed the mass joblessness, brutal evictions, soup kitchens, breadlines, or Hooverville; the region did, however, experience hard times

The Boothbay Region, the Great Depression, and the New Deal

A look at the Boothbay Harbor and Southport Annual Reports for the Depression Decade as well as the Boothbay Register confirms that behind the Lawnmeer and Newagen Inn’s fluffy curtains lurked Depression-era misery. Indeed, at least one Southport Hotel, the Cozy Harbor House, went bankrupt. The property was purchased by local sailing enthusiasts and became the clubhouse of the Southport Yacht Club.

In 1933 Lorena Hickok, a talented newspaper reporter who shortly became an intimate friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, joined a team of reporters enlisted by Federal Emergency Relief Administrator Harry Hopkins. Hickok in 1933 reported on Maine and toured the state’s harbor towns. She found thousands of families, eligible for federal relief, but not getting it. “A ‘Maine-ite,” she wrote, “being the type of person he is, would rather starve than ask for help. In fact, his fellow citizens would expect it of him. It is considered a disgrace in Maine to be ‘on the town.’”v / vi

From its genesis in 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, via programs such as the National Recovery Act (NRA), the Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA), the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Civil Works Administration (CWA), and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and Public Works Administration (PWA) addressed the desperate needs of a nation stricken by an unprecedented financial crisis, and bridges were very much part of the infrastructure built during the 1930s by work relief agencies such as the CWA, WPA and the PWA.vii

From the beginning as early as 1933, Boothbay Harbor and Southport residents benefitted from New Deal Public Works projects. In the Boothbay Region the late 1930s the WPA in funded work on about 30 projects including extensive street and infrastructure work installing culverts and work laying new pipe lines for the Boothbay Harbor Water Department. On October 21, about 30 men toiled on three Harbor projects at the United States Fish Hatchery on McKown Point, and doing road construction at Lobster Cove and a project building sidewalks in Mill Cove. In another celebrated Harbor project, the PWA joined with the State of Maine in building the Maine State Lobster Hatchery on McKown Point. viii

That same Register article - that featured WPA projects underway during the winter of 1938-1939 - ended by revealing that “In approximately a month, work on the new PWA-funded $178,000 Boothbay Harbor-Southport bridge will begin. Officials of both towns feel that construction of this bridge will completely solve the unemployment problems of both towns for several months [italics added].” ix

Southport’s existing 1916 wooden bridge had never met the standard of being a durable, reliable span, one capable of comfortably bearing a bus loaded with children. It was not until the 1930s that conditions ripened for its replacement. In mid- March 1936, according to the Register “Many Maine Cities and Town Suffer[ed] [the] Worst Floods in History.” Rising flood waters in the Kennebec River carried “great ice flows” threatening Bath’s Carlton Bridge, and Main Streets in Gardiner and Hallowell. While the Southport Bridge survived that spring flooding, it did so only miraculously; the bridge, in fact, sustained some damage. Months later, another serious incident facilitated and amplified the growing call for a new bridge. Early Sunday morning, September 5th, 1937, a fire in Decker’s Cove “of undetermined origin” totally destroyed the Southport Casino – with its store, post-office and popular dance pavilion- that adjoined the wooden Boothbay/Southport bridge. Owned now, not by the Thompsons, but by Saul Hayes of Hays Amusement Company, the dance hall in 1937 was one of the largest in Lincoln County. Obliterated by fire, the Hays’ Pavilion structure would no longer obstruct the building of a new steel swing bridge. In February 1939, the Southport Selectmen voted to purchase both the Hays property and also an adjoining strip of Thompson-owned land as “necessary for the land and proper approach to the southerly end of said. . . proposed Boothbay Harbor-Southport Bridge.” x

The New Deal, and the New Bridge

Unquestionably, by 1935 Southport’s wooden bridge not only needed to be rebuilt, but also the timing seemed propitious. Two Southport selectmen, Jason Thompson and W.G. Love, in November 1937 had attended a special session of the Maine Legislature, where they introduced a “resolve” imploring funds “for the construction of a new bridge between Southport and Boothbay Harbor and that the state supply 60 percent of the funding, the county [Lincoln] 20 percent, and Boothbay Harbor and Southport 10 percent each.” xi

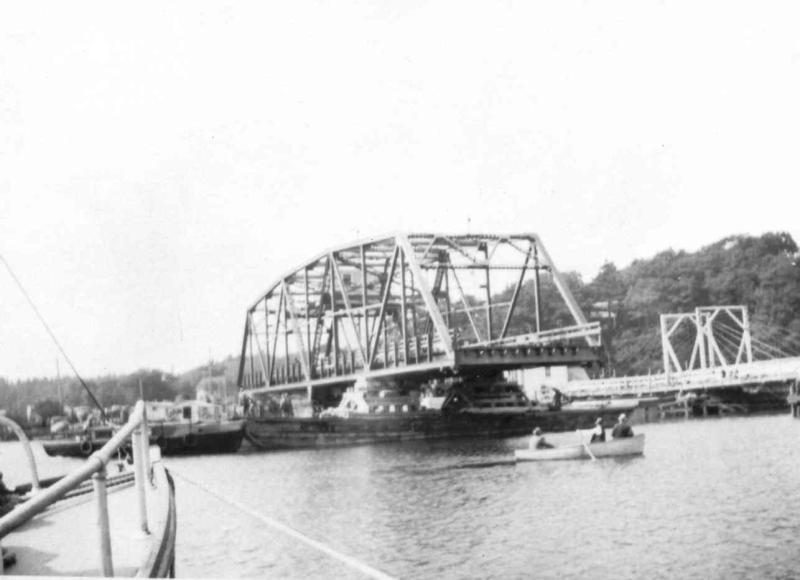

This new Southport Bridge envisioned by the Maine State Highway Commission would be a steel bridge - not wooden- defined as a 374-foot-long, standard design “Polygonal, Warren Through-Truss, ‘Movable’ Swing Bridge,” with a center bearing pivot pier to be planted deep into the seabed of Townsend Gut. Between 1920 and 1955 the Maine State Highway Commission. designed and built 85 such steel truss bridges. Southport’s bridge with its 178 feet swing span, would be one of Maine’s largest through-truss, swing bridges.xii

Initial engineering surveys estimated the cost of such a new steel truss bridge built at the site of the “existing” wood bridge to be $113,000. Shifting the site slightly eastward to enable utilization of the old bridge during construction raised the estimated cost to $130,000. [The final cost, once the low bids for construction were accepted, was $180,000.] Boothbay Harbor, nevertheless, balked at paying its 20 percent share as set by the 1927 Maine Bridge Act, a percentage share calculated on the basis of the town’s property valuations, and, thus, a figure that for Boothbay Harbor, naturally, stood well above Southport’s much lower property evaluation. The Harbor, moreover, viewed Southport as the main beneficiary of a new bridge. xiii

A July 1938 meeting on the stalled Southport Bridge issue held with the State Highway Commissioners, delegates from Boothbay Harbor, Southport, and Lincoln County, made any final agreement on the Construction of the proposed new Southport steel truss bridge contingent, number one, on securing a Public Works Administration (PWA) grant to cover 45 percent of the bridge cost (not to exceed $65,250!!!); and, number two, on fixing the Harbor’s share of the bridge cost at $7,500. In addition, the agreement stated that Southport pay its designated share, plus any sum beyond the harbor’s commitment of $7,500. The Highway Commission assumed responsibility for applying for the PWA grant. Using the final cost figure of $180,000 [there were cost over-runs], Lincoln County paid $23,000 of the bridge cost; the state paid $75,750; the PWA $65,250; Southport, $8,600; and Boothbay Harbor $7,500.xiv

Bidding on the Bridge contracts was competitive. Among the bidders was American Bridge itself. For building the vital substructure to be erected beneath the waters of the gut, i.e., the massive 17 foot piling to support the central pivot pier, Wyman and Simpson of Augusta won the contract with its bid of $118,521. Lackawanna Steel Company of Buffalo, New York, at a bid of $71,277, successfully won the contract to build the steel truss swing span, as well as the east and west steel truss spans. The two winning bids raised the final bridge cost to just shy of $180,000. The cost actually rose. Lackawanna Steel almost immediately faced difficulties erecting the cofferdam and driving the 70 foot long steel pilings for the pivot pier and forced the Bridge Commission to add almost $5,000 to the cost.xv

The Trials and Tribulations of the Southport Bridge

The vital “draw span” was put in position around September 12th, 1939, and all bridge work was declared completed on December 29, 1939. The sparkling, new, thru-truss swing bridge spanning the gut featured a bituminous-covered wooden deck surface, with its huge, electrically-powered, geared pivot-pier protected by a heavy-timbered ice fender. Alas, its long-awaited opening begged several questions. Who was to operate the bridge? Where would the operator/s live? Who would pay for the cost of maintaining the all-steel swing bridge?

The new Southport-Boothbay Harbor thru-truss, swing bridge (State Highway Bridge No. 2789) officially opened in March of 1940 when young Norman Lewis and his family - jointly employed by both towns – assumed its operation. War already raged in Europe, and while America remained momentarily neutral, a pall of dread hung over vacationland. Nazi Germany had seized first the Sudetenland, then Poland, and in 1940 threatened England. Boat traffic in the “Gut” was minimal, and would remain that way for the next five years. No more than 400-500 boats a year passed under the new bridge during the war years.

During most of the war Norman Lewis (with occasional help from his wife Mildred) managed the bridge on a 24 hours a day schedule, and when Norman during 1945-1946 served in the U.S. Navy, Mildred operated the bridge alone. xvi The Lewis family in 1940 lived in the 2.25 story bridge-tenders house, the clapboard, frame, “four-square”-design house that adjoined the now demolished 1896-built wooden toll bridge.

Located on a State Highway, Route 27, in 1947 and in accordance with the Maine Bridge Act of 1947, the Bridge Division of the Maine State Highway Commission assumed ownership, maintenance, and operation of the Southport, Boothbay Harbor truss, swing bridge, including the bridge-tenders’ house. That same year, 1947, Norman Lewis returned from his service in the U.S. Navy. And, just as the towns had, the State Highway Commission between 1947 and 1970 continued to operate the new steel bridge using what it called “The Family Plan,” that is, employing Norman Lewis, his wife, and their growing family.

Although still viewed by many as a new bridge, in 1947 there were already problems with the bridge. Complaints first arose in the early 1960s about the rough surface of the bridge decking, the asphalt-covered planking that formed the bridge deck and in 1970 the Highway Commission raised the possibility of removing the rough, bumpy, asphalt covered wooden surface and installing an open steel grid surface. In response to objections that a steel grid deck posed problems for pedestrian traffic, the Highway Commission made plans to allocate space for a 3-4-foot side strip for pedestrians. Meanwhile, to render the old surface firmer, in 1971 the Highway Commission replaced the asphalt covered one-inch-thick 3” by 6” strip planking (where holes in the planking had appeared and been patched) with 2-inch-thick bituminous covered wood planking. Still the surface remained rough. Finally, in 1973, the wooden decking was replaced with the earlier proposed open steel grid surface. Due to structural shifting on the central pivot pier of the bridge, the steel grid surface itself remained still rough in 2021.xvii

Even more that the decking surface, the Southport bridge’s lighting and warning system early emerged as a key bridge issue, especially the tenders’ ability to warn motorists about imminent bridge openings. Bridge openings became more frequent after World War II, multiplying from a mere 500 a year in the 1940s to 444 alone in the month of July 1954. The bridge had opened in 1939 without any warning signs or signals, and in 1954 the Highway Commission at last installed “reflectorized” warning signs at both approaches. Three years later in 1957 the Commission wired the bridge for electric pier lights to warn boats approaching the span at night.xviii

A year later, in January 1958 an event occurred that made improved warning signals imperative. On a wintry January morning, replete with black ice, Southport school bus driver, Stuart Thompson, suddenly seeing the bridge unexpectedly opening, slammed on his brakes and skidded into the side of the bridge. Fortunately, no one was seriously hurt, Not until 1973 did the Highway Commission install the costly automatic gates and traffic signals at the Southport Bridge.xix

Beginning in July 1970, Norman Lewis, his twin son Duane, and an assistant, Roger Marr, all worked yearly 48 hours per week; Dwight Lewis, Norman’s other twin son, worked 48 hours weekly, but “Summer Only.” After endeavoring, but in vain, to sell the bridge tenders house for removal, the Commission in 1975 had the old, water-bereft structure demolished. xx

That year, 1975, tourism – the once fledgling industry, that now sustained the region – boomed. Since 1970 the three full-time Southport Bridge tenders, led by Norman Lewis, his son Duane, Roger Marr (plus the other twin, Dwight, but only in the summer) had been reinforced during those busy summer months by paid “School Youngsters.”

Suddenly, state budgetary problems in the June of 1976 dispensed with the “youngsters.” The Register’s Mary Brewer vented the region’s deep displeasure at now having a solitary individual operate the bridge during the peak hours of the summer season. “Southport’s bridge is the second busiest bridge in Maine,” wrote Brewer, with thousands of openings a year. “When a boat signals that it wishes to pass through, the bridge tender must go to the Boothbay Harbor end of the bridge, turn on the signal light to warn approaching traffic, close the gate, go to the Southport end of the bridge, about 200 feet away, and close the gate to traffic, the return to the center of the bridge, climb the twenty steps to the control room, and open the bridge for the boat to pass through.” xxi

In their outrage, the complaining Southporters no longer referenced the island’s glorious maritime past. Instead tourism took center stage, the grim prospect of summer bridge delays inconveniencing, perhaps even discouraging the critical summer crowd. An irate Southport resident, George Pierce, dashed off a June 11, 1976 missive to Maine Governor James B. Longley berating the “reduction in services” as “Intolerable” and an “injustice.” He pleaded that he had been a “loyal” Longley “supporter,” but, perhaps no longer. “Southport,” he wrote, “is a busy place during the summer what with our several motels and hotels and a great many resident summer people to say nothing of the year-round residents who are employed in the Boothbay Harbor region, and, of course, many tourists and guests at our homes.” xxii

In 1978 a host of petitions arrived in Augusta from both Southport and Boothbay Harbor constituents all demanding that to relieve the waiting times for both boat and automobile traffic at the Southport Bridge the Highway Department “construct an automatically operated gate system for the subject bridge.” Two years later beleaguered department engineers responded to the outcry saying that they understood “the automatic gate systems to be part of other improvements and the funding for the gates would be provided under the [new] Bridge Act [italics added].” In other words, be patient, help is coming. xxiii

Under that Bridge Act the planned rehabilitation of the Southport Bridge grew increasingly comprehensive. By June 1981 the Department’s list of Southport bridge improvements embraced updating all the electrical equipment, rehabilitating every piece of machinery, installing a new submarine cable, finally also installing the new “automatic” gates, replacing the fender system, and improving the bridge approaches. xxiv

As part of the planned, 1985-1987, bridge rehabilitation, the Maine Department of Transportation (once the State Highway Commission) retained a consulting firm, Milton C. Stafford, P.E. of Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, to thoroughly examine the existing “rack and pinion” cast tooth gear system, and electric motor drive that opens and closes the swing bridge, especially the condition of the “steel cast tooth rack” so stressed under full torque pressure. Stafford found the rack teeth possessed only 65 percent of the expected strength to meet the standards of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). However, Stafford found it “doubtful that the type of [gear] wear observed has reduced the beam strength of the teeth substantially.” Maine DOT disagreed, and in February 1985 called for the replacement of the rack and pinion system (estimated cost $55,000) to be made part of the contract awarded in February 1987 for the full rehabilitation of the Southport Bridge. The project was scheduled for completion in July 1987. In May 1987 the bridge was closed to highway traffic for up to 4 hours daily; the swing span was inoperable for 6 weeks. The work was not fully completed until September of 1987. xxv

Therefore, it was the top heavy wooden beam on the northeast side of the Southport Bridge’s fender – part of the recently rehabilitated Southport Bridge – that on August 18th, 1989, at exactly 11:30 PM, that David Winslow at the helm of a Winslow tugboat smashed against. In the pitch darkness Duane, perched in the bridge operator’s office heard and felt the crash. Duane yelled at Winslow to “STOP.” Winslow from his tug then yelled back that “he didn’t have time to stop;” “Send me the bill.”xxvi

References

i For a source on the Brooklyn Bridge and on James Eads St. Louis span, see David McCullough, The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972).

ii Gardner, Ruth Leppe, Southport Historical Series, found in Hendricks Hill Museum, Southport, Maine.

iii “Norman Lewis of Southport Oversees Operation of Maine’s Second Busiest Bridge,” Boothbay Harbor Register,” n.d., found in “Southport File,” Boothbay Harbor Historical Society, Boothbay Harbor, Maine.

iv Phyllis Cook, BHR, 7/03/2008; “Duane and Dwight Lewis”, BHR, 7/03/2008.

v Report, Lorena Hickok to Harry L. Hopkins, September 21-29, 1933, found in Richard Lowitt and Maurine Beasley, eds., One Third of a Nation: Lorena Hickok Reports on the Great Depression (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981) p. 36; also Judd, et.al. Maine, p.516.

vi On Overseers of Poor, See Annual Report of Boothbay Harbor, Maine, 1933-1934, 1934-1935, 1935-1936; and Annual Report of the Town Officers of the Town of Southport, Maine, 1933-1937; On the Anti-New Deal editorial policy of the Boothbay Harbor Register, see “Let us Face the Fact; “Let us have not misunderstanding . . . make no mistakes. The big issue of the State election of Monday, September 14th is THE NEW DEAL,” BHR, 9/11/1936; and “Where Does the Money Come From?” BHR, April 3, 1936. Here the editorialist wrote that “All the money now being raised for work relief. . . is the people’s money, not the federal government’s money, not the president’s money . . ..”

vii On the Great Depression and the New Deal, see Robert S. McElvaine, The Great Depression: America, 1929-1941 (New York: Random House, 1984); Bauman and Coode, In the Eye of the Great Depression; on the New Deal, passim; also see the classic, William F. Leuchtenberg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (New York: Harpers, 1963).

viii On the lobster hatchery and other Boothbay Region WPA projects, see “Employment Prospects Here Bright for Winter Months,” BRH, 10/21/1930; also “PWA Grants $12,981 For New Lobster Rearing Station Here,” BHR, 12/2/1938; on WPA work on Harbor water lines, see Fiftieth Annual Report, Boothbay Harbor, Maine (1939); on WPA night school, see BHR, January 28, 1938; also “Many Workers to Get Social Security Funds,” BHR, 1/28/1938.

ix “Employment Prospects Here Bright,” BHR, 10/21/1938, p.1.

x Clifford, 226; see, also, “Fire Razes Southport Casino, Region’s Largest Dance Hall,” BHR, September 10th, 1937; “Secretary of the [Southport] Board of Selectmen, to the Town of Southport, February 18, 1939, stating purchase of Hayes and Thompson land, found in Maine State Highway Commission Records [Hereinafter, MSHCR], found in the Maine State Highway Commission archives, Augusta, Maine.

xi BHR, 11/19/1937.

xii Maine DOT Historic Bridge Survey, Phase II, Final Report (Augusta, Maine DOT, 2004); Maine DOT, “Summary of Scope of Services, Southport Bridge, Southport-Boothbay Harbor, Project BH-000S (49).

xiii MSHCR, Memo, July 13, 1938, pp. 6-8; also see Highway Com. Records, September 7, 1938, pp. 15-18; see also “Southport Selectmen Seek Funds for Bridge,” BHR, November 19, 1938.

xiv MSHCR, Memo, September 7, 1938, attaching letter from H.A. Gray, Assistant Administrator, PWA, to State of Maine, August 25, 1938, outlining PWA’s terms for supporting grant to Maine for Southport bridge; Highway Com. Records for 7/13/38, p. 7. Document details county and Boothbay Harbor terms for supporting bridge construction; On PWA participation, see Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works Administration, August 25, 1938, PWA Form 230, Project, Applicant: State of Maine Highway Commission, $65,000, found in Records of PWA, RG 135.2, found in National Archives and Record Service, College Park, MD; see also Clifford, p. 2267; and “Southport Bridge Question Again Before Local Voters,” BHR, September 23, 1938, p.1.

xv On contract bids, etc., see Highway Com. Records, 1938-1939; on piling problems, see Highway Com. Records, June 27, 1939; “Some Pilings Would Not Go Down,” BHR, February 3, 1939; “Southport Column,” BHR, July 21, 1939.

xvi “Southport Bridge Tenders Being Kept Very Busy,” BHR, 1969, clipping found in MSHCR.

xvii Christine Duke to Max Wilder, November 29, 1962, MSHCH; on the “recently redecked” Southport Bridge, and the pedestrian issues with steel grid flooring and the need for a pedestrian walkway, see SA.R. Sirois to Clifford Buck, April 7, 1971, MSHCR; on authorization request for grid flooring on Southport Bridge, see Sirois, to Martin C. Rissel, November 14, 1972, MSHCR; The steel grid flooring 5-inch, Weldlock, product, called “Rectagrid,” was produced by the Reliance Steel Corporation in McKeesport, Pa., outside of Pittsburg; also, on “still rough,” see Maine DOT to Gene Huskins, Mary L. Kostella, and Gerald L. Gamage, October 11, 1988, in MSHCR.

xviii Max Wilder to Jason Thompson, Southport Town Clerk, August 12, 1954; Minutes of the Maine Highway Commission, March 13, 1957.

xix Max Wilder, to Hon. George Rankin, Jr., February 12, 1958, MSCHR; Al Godfrey and A.R. Sirois, Memo on Southport Bridge, February 13, 1973, MSHCR

xx Inter-Departmental Memorandum, Abel R. Sirois, to Martin C. Rissel, July 28, 1970, MSCHR; on the disposal of the tenders’ house, see A.R. Sirois to Martin Rissel, July 10, 1973; and Sirois to Harvey Winn, March 12, 1975, MSCHR.

xxi Mary Brewer, “It May Be a Long Wait for Motorists at the Southport Draw Bridge,” BHR, June 28, 1976; also, Larkin, “Like Father, Like Sons,” 29034.

xxii George E. Pierce, Jr. to Hon. James B. Longley, June 11, 1976, found in MSHCR.

xxiii See Interdepartmental Memo, T.H. Karasopoulos, Bridge Design Engineer, to A.R. Sirois, October 3, 1980, MSCHR.

xxiv Memo from Ted Karasopoulos, and E.B. Barnard, on “Boothbay Harbor-Southport, Southport Bridge, June 22, 1981, MSHCR.

xxv Milton C. Stafford, to Maine Department of Transportation, February 2, 1985, “subject: Southport Bridge Span Drive,” MSHCR; Larry L. Roberts, Assistant Bridge Design Engineer, to Milton Stafford, February 7, 1985; Gary Hoar, to Town of Southport, February 10, 1987, announcing award of contract for rehabilitation work; see, State of Maine Inter-Departmental Memorandum, Larry Roberts to Robert Phillips, August 18, 1987, all in MSCHR.

xxvi State of Maine, Inter-Departmental Memorandum, Duey Graham to Thomas Reeves, August 21, 1989, “Potential Tort Case,” MSCHR.