Sternman

I was 16 years old when my dad, a great believer in the virtues of me doing hard work, talked me into taking a job as sternman on a lobster boat.

The lobsterman, I’ll call him Arlo, fished a traditional wooden-hulled boat and believed that if God had wanted us to have fiberglass boats, He would have made fiberglass trees.

He’d pick me up at 4 a.m. and drive to the dock. By 4:30 a.m. we’d be pitching rotting redfish carcasses into bait tubs. If you weren’t fully awake at this point, the stench would do the trick. We’d cast off and head for the open ocean before sun-up.

The entire time barely a word was spoken. Arlo might offer a mumbled “Munin’” as I got into his truck, but basically compared to him the “man of few words” is a regular chatterbox, so we stood silently on deck smoking cigarettes in the pre-dawn dark.

Sunrise found us a mile or two offshore hauling strings of six heavy wooden traps, backbreaking work with little room for error. Arlo would ease the boat to within a few feet of a jagged, rock cliff, feathering the throttle with one hand while holding the gaff in the other.Then he’d snag the buoy, haul it in and wrap the line around the winch hanging outboard over the starboard rail. Then he’d kick it into high gear, the engine whine rising a notch. As the boat rocked to starboard the line grew taught, sizzling up from the depths and flinging a fine salt mist in my face.

When the first trap surfaced I was on it, hoisting it aboard, opening the door, tossing sculpins, sea snails and urchins overboard. I’d measure and toss back the shorts and breeders, heaving the keepers into a crate at the stern. That winch was still cranking full throttle as I slid the baited trap onto the transom just as the next one arrived.

Baiting these old wooden traps went like this: open the trap, take the bait iron (like a long darning needle with a hole in the sharp end), thread a cord through the eye of the iron, and ram it straight through the empty eye sockets of a half dozen stinking redfish then hang the bait inside.

At around noon we’d break to scarf down a couple of sandwiches and a Coke. We sat on the transom, eating in silence, staring at the endless sea and sky, not socializin’, just takin’ a lunch break. Then back at it. Hard.

As the summer flew by I grew stronger and more confident, made good money and even managed to save some of it, due mostly to the fact that I couldn’t stay awake past 6 p.m.

My last day as a sternman was one of those postcard-gorgeous Maine days. But around noon the engine abruptly shut down and I thought, “Hmm, this isn’t a good sign.”

Offering no explanation, Arlo snagged one of our buoys, rigged a makeshift mooring, ducked down the hatchway and rummaged around in the galley, emerging a moment later with a battered metal cook pot. He fastened a line to the handle, tossed it over the side and brought it back half-full of seawater.

As he lit the galley stove and put the pot on to boil. I was starting to get the idea.

Grinning at me for the first time ever he asked, “Just how many of these crawlers you s’pose you can eat, anyway?”

I was caught off-guard. That was an incredibly long speech for Arlo. “Oh, I dunno, maybe two or three?”

He snatched a half-dozen lobsters, tossed them into the pot of steaming water, sat down opposite me and, lighting a cigarette, began to talk.

He told me I’d done a darned good job as his sternman. That took more words than he’d used all summer, but he didn’t stop there. He asked me about my plans. Was I going to play football for the Seahawks?

I can’t recall his questions much less my answers, but I’ll never forget the way I felt that afternoon. Sitting on deck in the late summer sun, it dawned on me that we were just talking like men talk to one another, easy, relaxed, man to man. It was a new and marvelous sensation.

We ate our fill, casually tossing lobster shells over the side, as a growing flock of gulls materialized from nowhere to fight over the remains. One last cup of coffee and a smoke and Arlo fired up the engine and headed in.

Back at the dock, after unloading the catch, stowing the gear and hosing down the boat for the last time, Arlo reached out and shook my hand. His felt like a rough chunk of rock maple.

He looked me right in the eye and said, “If you ever want to be a sternman again, you come see me.”

I never did. If nothing else, that summer motivated me to pursue a career that didn’t involve hard physical labor.

I did stop by and visit him a few times over the years. He was always hard at work so the visits were short, but, although he never said so, I could tell that he was genuinely pleased to see me. That silent message, coming from a Maine lobsterman, is high praise indeed.

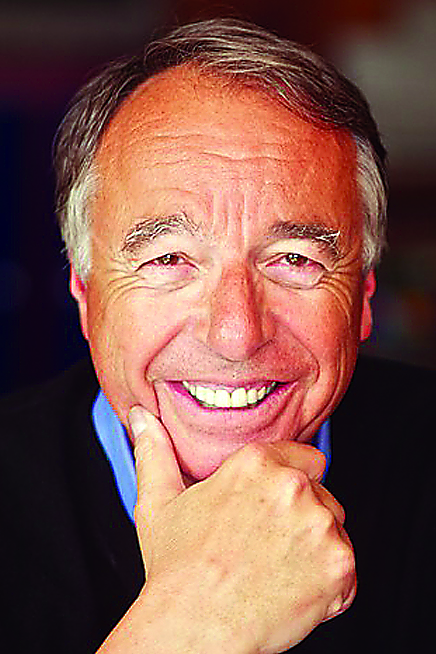

Tim Sample will be performing at the Boothbay Opera House, where he first appeared as a teenage rock 'n' star, on Thursday, June 28, at 7:30 p.m. For more information, call the Opera House 633-5159 or visit their website.

Address

United States