Scientists research the movement of squids at the Darling Marine Center

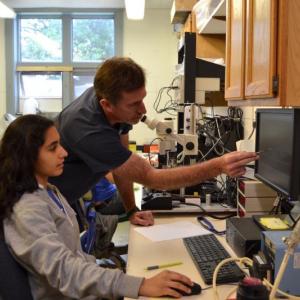

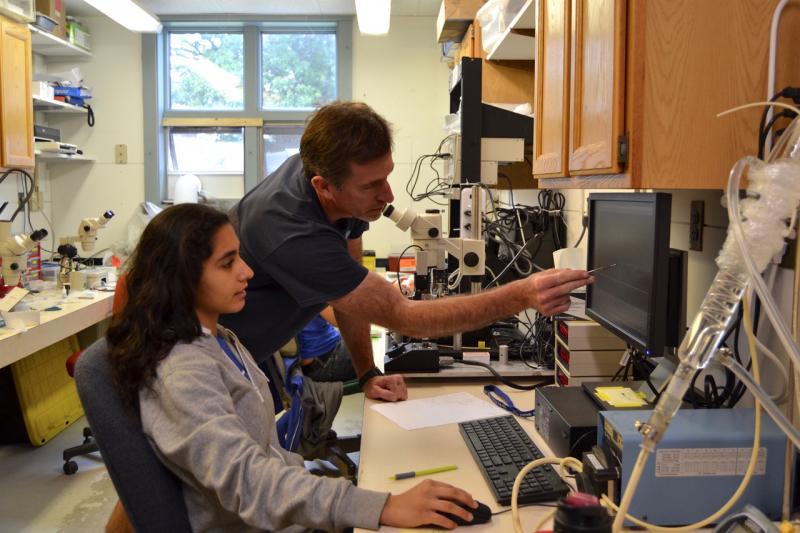

Dr. Joe Thompson and his intern Rashi Anand conducting an experiment on squid muscles at the Darling Marine Center in Walpole. Courtesy of Aliya Uteuova

Dr. Joe Thompson and his intern Rashi Anand conducting an experiment on squid muscles at the Darling Marine Center in Walpole. Courtesy of Aliya Uteuova

Dr. Joe Thompson and his intern Rashi Anand conducting an experiment on squid muscles at the Darling Marine Center in Walpole. Courtesy of Aliya Uteuova

Dr. Joe Thompson and his intern Rashi Anand conducting an experiment on squid muscles at the Darling Marine Center in Walpole. Courtesy of Aliya Uteuova

This summer, the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center is hosting a team of researchers for a collaborative study of squid locomotion. The goal of the project is to identify critical features of muscles that control maneuvering performances in squid.

The idea for this was research sparked five years ago, during a conversation between three scientists: Ian Bartol, Paul Krueger and Joe Thompson. The topic of conversation was the unique and amazing maneuverability of squid.

"Squids are fascinating animals to study because they use two separate but coordinated propulsive systems to swim and turn: a pulsed jet and complex fin movements. Together, these systems afford squid incredible locomotive flexibility, allowing them to navigate complex habitats, change direction rapidly, or even ascend/descend vertically," Bartol said.

Bartol is a faculty member at the Old Dominion University specializing in biomechanics of marine animals. Paul Krueger, professor of mechanical engineering at the Southern Methodist University, shares Bartol’s interest in studying maneuverability.

Joe Thompson is a professor of biology at the Franklin & Marshall College and long-time summer researcher at the DMC.

This collaborative project is tackling mobility in Atlantic longfin squid (Doryteuthis pealeii) from different angles. Squids maneuver in order to capture prey, elude predators, and compete for access to mates. While Thompson’s team of two undergraduate interns, Rashi Anand and Hallie Keatley, is looking at the muscles of the fin and arms, Bartol’s lab is applying hydrodynamics to study the fin motion. A mechanical engineer, Krueger provides expertise in movement of fluids around fins and arms of squid, as well as jet locomotion.

“There is so much you can gather from invertebrates,” said Anand, a biology major at Franklin & Marshall College. “Even though the anatomy of humans and squids are different, you can apply so many things from invertebrates to human body.”

Initially, the most challenging parts of the research for Anand and Keatley were learning to perform the dissections, preparing the muscle tissues, and understanding the electronics used to measure muscle contractile properties. “There was a lot of trial and error,“ Anand said.

The underlying question of this study is how the muscle physiology changes with growth, and whether these changes affect squids’ maneuvering performances.

“In addition to understanding general principles of muscle physiology that apply to all animals, perhaps the principles discovered in squids can also improve performance for remotely operated vehicles,” Thompson said.

“One of the reasons I love working with undergrads is watching them metamorphose from novices into skilled and competent scientists. That’s quite special,” Thompson said.

This is Thompson’s thirteenth year carrying research at the DMC.

“I’ve worked at a few different marine labs,” Thompson said. “The DMC is unique because the community is small enough to allow you to get to know everybody but large enough to make connections with people studying questions in basic and applied science. There aren’t a lot of places where you can have all this variety and a strong sense of community.”

Located in Walpole, the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center is an active center of marine research, education, and community engagement. DMC scientists and students study coastal and marine ecosystems, as well as the human communities that are a part of them, in Maine and around the world.

Event Date

Address

United States