Ocean acidification panel calls for action to address threat

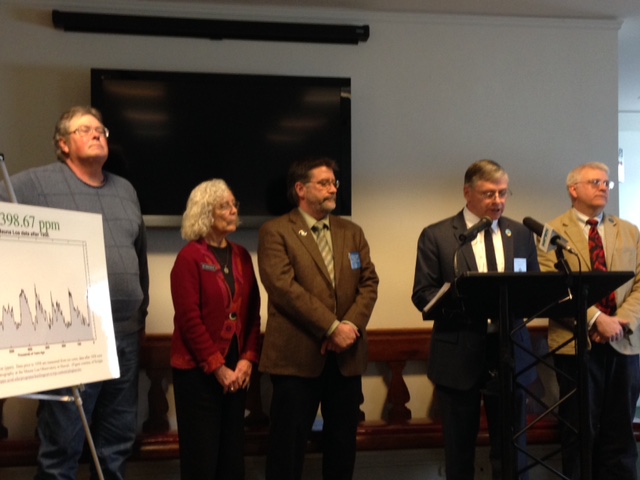

The Ocean Acidification Commission on Thursday presents its report to the public and unveils four bills for the legislative session (from left: Richard Nelson of Friendship, Rep. Joan Welsh, D-Rockport, Rep. Wayne Parry, R-Arundel, Sen. Chris Johnson, D-Somerville, and Rep. Mick Devin, D-Newcastle). Courtesy of Ann Kim

The Ocean Acidification Commission on Thursday presents its report to the public and unveils four bills for the legislative session (from left: Richard Nelson of Friendship, Rep. Joan Welsh, D-Rockport, Rep. Wayne Parry, R-Arundel, Sen. Chris Johnson, D-Somerville, and Rep. Mick Devin, D-Newcastle). Courtesy of Ann Kim

The Ocean Acidification Commission on Thursday presents its report to the public and unveils four bills for the legislative session (from left: Richard Nelson of Friendship, Rep. Joan Welsh, D-Rockport, Rep. Wayne Parry, R-Arundel, Sen. Chris Johnson, D-Somerville, and Rep. Mick Devin, D-Newcastle). Courtesy of Ann Kim

The Ocean Acidification Commission on Thursday presents its report to the public and unveils four bills for the legislative session (from left: Richard Nelson of Friendship, Rep. Joan Welsh, D-Rockport, Rep. Wayne Parry, R-Arundel, Sen. Chris Johnson, D-Somerville, and Rep. Mick Devin, D-Newcastle). Courtesy of Ann Kim

The Commission to Study the Effects of Coastal and Ocean Acidification on Commercially Harvested and Grown Species on Thursday presented its report to the public and unveiled four proposals for the current legislative session that are informed by the panel’s work.

“Maine is taking the lead on ocean acidification on the Eastern seaboard. We understand just how dangerous it is to our marine environment, jobs and way of life,” said Rep. Mick Devin, D-Newcastle, co-chairman of the panel and sponsor of the legislation that created it. “It isn’t just valuable shellfisheries that are at risk, but other parts of our economy like tourism. No one visits the Maine coast looking for a chicken sandwich. Let’s make sure visitors can have a lobster roll, a bowl of clam chowder, a bucket of steamers or a platter of Damariscotta River oysters on the half shell when they come to Maine.”

The 16-member panel, the first of its kind on the East Coast, brought together fishermen, aquaculturists, scientists, legislators and representatives of the executive branch. The commission reviewed the science on ocean acidification and made recommendations on how Maine should address the threat that changing ocean chemistry poses to its marine ecosystem and economy. The commission’s report won the unanimous support of its bipartisan and diverse members.

“Together, we accomplished a really detailed examination of what we know about ocean acidification, what we still need to know more about and other recommendations to both understand and do something about ocean acidification. It’s a much needed first step,” said Sen. Chris Johnson, D-Somerville, co-chairman of the commission. “A key thing I will tell you is that ocean acidification is real and already impacting some Maine fisheries.”

The recommendations offer a comprehensive approach that fall under six goals: (1) invest in Maine’s ability to monitor and investigate the effects of ocean acidification; (2) reduce emissions of carbon dioxide; (3) reduce local land-based nutrients and organic carbon contributions to acidification; (4) increase Maine’s capacity to mitigate, remediate and adapt to the impacts of ocean acidification; (5) educate and engage stakeholders, decision-makers and the public and empower them to take action; and (6) maintain a sustainable and coordinated focus on ocean acidification.

Legislative members of the panel have introduced four bills informed by the report: a $3 million bond proposal for a monitoring program to quantify acid inputs from atmospheric carbon dioxide, river discharges, point sources and chemical reactions affecting clam flats. (Sponsored by Rep. Wayne Parry, R-Arundel); a measure to help improve land for farming and implement management practices for the watershed. (Sponsored by Sen. Chris Johnson, D-Somerville); a measure to replace inadequate septic systems that impact nutrient loading and the bacterial contamination of watersheds and bays. (Sponsored by Sen. Chris Johnson, D-Somerville); and a measure to continue the work of the ocean acidification commission, with a sunset of three years. (Sponsored by Rep. Mick Devin, D-Newcastle).

“As someone who has worked on the water for two decades, I can say firsthand that we need to know where our problem spots are so we can mitigate them,” Rep. Wayne Parry, R-Arundel, a commission member and working lobsterman, said of his monitoring bond bill. “It’s critical that we know where, when and how this acidification is taking place.”

Richard Nelson, a Friendship lobsterman and commission member, noted that fishermen, like scientists, must observe their natural surroundings and track various elements of nature as they change over time.

“And although we are keen observers of these trends, we are now realizing that the health and well-being of our fisheries and that of our ocean are not just affected by the actions of a few fisherman or the decisions by our fisheries managers, but by a broad scale of societal choices, from local to global, about energy, runoff and waste water, as well as maintaining and restoring the natural systems of our coastal and ocean environment,” Nelson said.

Another commission member, Bill Mook of Mook Sea Farm, an oyster farm in Walpole, said the panel’s work is just the starting point.

“Maine’s marine resources-based businesses like mine need a lot of information so that financial decisions are based on calculated risks rather than gambles,” he said.

Atmospheric carbon dioxide is the greatest factor behind ocean acidification.Nutrient and carbon dioxide from land-based point and non-point sources, such as municipal wastewater treatment facilities, septic failures and runoff, are additional drivers of acidification for estuary and near-shore waters.

The combination of carbon dioxide and seawater forms carbonic acid, which impact species including clams, lobster, shrimp and cold water coral.

Ocean acidification is taking place at a rate at least 100 times faster than at any other time in the past 200,000 years, the commission noted. The Gulf of Maine is more susceptible to ocean acidification than other regions in the United States.

“Ocean acidification is not a hopeless issue. I assure you there is hope for Maine’s coastal health and economy,” said Dr. Meredith White, a commission member and biological oceanographer at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences. “Ocean acidification is a global problem, but it can best be addressed at a local level. Maine has taken a historic first step in addressing the issue and that makes it all the more likely we will be prepared to face this challenge head-on.”

The commission’s report can be accessed online at www.maine.gov/legis/opla/Oceanacidificationreport.pdf.

Event Date

Address

United States