Lobster trap recycling program expands to Boothbay region

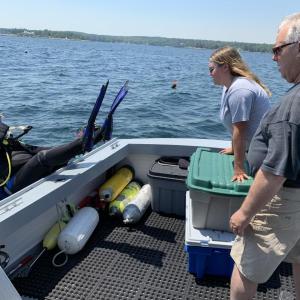

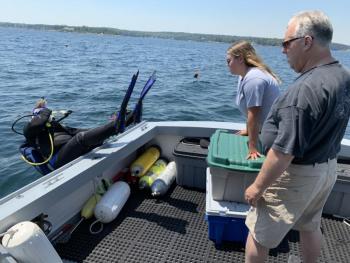

OceansWide founder and president Campbell “Buzz” Scott and assistant Celia Philbrick watch diver Elizabeth Foretek enter Townsend Gut to search for lost steel lobster traps. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide founder and president Campbell “Buzz” Scott and assistant Celia Philbrick watch diver Elizabeth Foretek enter Townsend Gut to search for lost steel lobster traps. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide divers Elizabeth Foretek and Matt Louis discuss a dive for ghost lobsters traps in Boothbay Harbor. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide divers Elizabeth Foretek and Matt Louis discuss a dive for ghost lobsters traps in Boothbay Harbor. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide diver Matt Lous heads into the water searing for ghost lobster traps. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide diver Matt Lous heads into the water searing for ghost lobster traps. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide founder and president Campbell “Buzz” Scott and assistant Celia Philbrick watch diver Elizabeth Foretek enter Townsend Gut to search for lost steel lobster traps. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide founder and president Campbell “Buzz” Scott and assistant Celia Philbrick watch diver Elizabeth Foretek enter Townsend Gut to search for lost steel lobster traps. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide divers Elizabeth Foretek and Matt Louis discuss a dive for ghost lobsters traps in Boothbay Harbor. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide divers Elizabeth Foretek and Matt Louis discuss a dive for ghost lobsters traps in Boothbay Harbor. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide diver Matt Lous heads into the water searing for ghost lobster traps. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

OceansWide diver Matt Lous heads into the water searing for ghost lobster traps. BILL PEARSON/Boothbay Register

The Gulf of Maine is full of ghosts. No, they’re not spooks or goblins, but rather lost steel lobster traps separated from their buoys. Unlike their wooden predecessors a generation ago, which dissolved into the salt water, these steel structures collect on the ocean’s bottom.

That was until OceansWide, a non-profit organization, began doing something about it. Last year, OceansWide processed 6,000 recycled lobster traps in Gouldsboro. Campbell “Buzz” Scott founded OceansWide to teach youth about the ocean through deep sea exploration. In 2018, Scott became concerned about a mounting number of steel lobster traps off Matinicus Island which led to his lobster trap recycling program.

In 2020, OceansWide began removing ghost lobster traps off the coast of Gouldsboro with plans for expanding the program into other Down East locations in Jonesport, Vinalhaven and Matinicus Island. But an article in a Maine fishing journal resulted in bringing the recycling program to the Boothbay region. A local benefactor read the article which brought the recycling program to Townsend Gut this spring. ”It’s a concerned family who wishes to remain anonymous,” Scott said. “They read about the program, and contacted us about doing this in Townsend Gut.”

So in April, Scott began bringing his lobster trap recycling operation to Boothbay Harbor. His crew is currently surveying Townsend Gut for ghost traps. Scott starts his day around 6 a.m. Mondays through Fridays with scuba divers surveying the local waters. Divers use GIS (geographic information system) mapping for recording the number and location of ghost traps. So far, OceansWide has found an unexpectedly large number of ghost traps. “The most surprising thing, so far, is the number. From the bridge to mouth of the gut, we’ve found over 200 traps. I figured there would be a lot, but not this many,” he said. OceansWide is also surveying outside Townsend Gut. Scott reports the survey has counted over 400.

The survey ends in June. In September, the project resumes. In October, November and December, OceansWide will begin hauling the traps out of the water. OceansWide uses two to four divers per day. Elizabeth Foretek is one of the divers. She sees the accumulation of traps concentrated on one another as one of the project’s major challenges. “They’re all piled up on top of one another. The question is how many can we pull out safely. Can we do it one at a time or drag them up in a jumble?”

In Gouldsboro, OceansWide deposited ghost traps at a local recycling center. The stripped-down traps were fed into a crusher known as the “lobster’s revenge.” Scott plans on depositing Boothbay region ghost traps at Robinson’s Wharf before taking them away for processing. He is still looking for a local recycling center to accept the scrap metal. “We will take a look at them to see which ones can be salvaged. The ones that can’t will be fed to the crusher,” he said.

OceansWide began as a way for Scott to follow advice from two mentors. Scott was told as a young adult to “Go out into the world, and make it a better place.” One mentor was a Matinicus Island fisherman. At age 27, Scott stopped fishing off Matinicus Island, and joined the U.S. Navy. He later found employment at Monterey Bay Aquarium where he met David Packard, co-founder of Hewlett-Packard. “They both encouraged me to spread my wings and make the world a better place. David was a good friend, and shortly after that conversation I began OceansWide,” he said.

OceansWide is based in Newcastle where Scott, 60, now lives. OceansWide uses scuba diving and remotely operated vessels in teaching students about the ocean through deep sea exploration. The program also teaches students a practical use of math and writing. “If you want to keep a journal, then you better know how to write one,” he said. Scott knew his organization would be an ideal vehicle for the lobster trap recycling program. “We have divers who can explore as low as 30 feet below the surface, and an ROV which can go 300 feet below,” he said.

In starting his nonprofit, Scott describes his motivation as repaying society for a rewarding life. “I’ve had a wonderful life and I wanted to give something back.”

Event Date

Address

United States