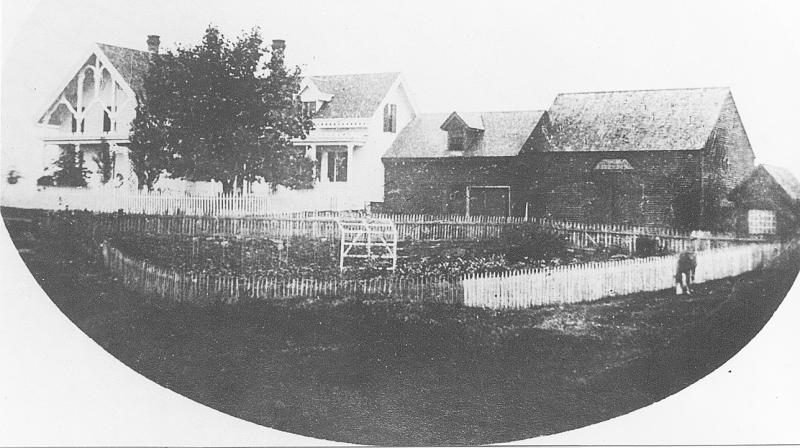

The house on Barlows Hill

Robert and Sarah Montgomery were the first permanent settlers in East Boothbay in 1730, locating at the end of Barlows Hill Road on top of Barlows Hill. I'm using the latest names for the hill and village, which have gone through about four different ones; roads were not named at all until the late 1800s.

They settled very near a site chosen by the 1600s settler, Henry Champnoise, building a house there and controlling much of the east side of peninsula. I'm unsure if they first had a log house, though that was commonly the earliest dwelling. In Boothbay nearly everyone farmed as well as going to sea or carrying on a trade that supplied some cash. For Robert Montgomery, that was weaving; later it was generally sawmills and gristmills for the family until the 1820s.

The Montgomerys and fire

By 1772 their son John had the house, then a frame timber-built dwelling. John probably farmed and worked at the family tidemill on the millpond. The house went to John's son Nathaniel in 1803. Nathaniel's great-granddaughter, Bernice Race Chesebro, wrote (thank you, John Chesebro!) that Nathaniel built a house on the site. That would be the second or third Montgomery house there, built during Nathaniel's 40 years of ownership. Though Nathaniel, principally a farmer, deeded the house to his sons in 1842, it stayed in his tax column.

In the mid-1850s, when the house passed into the tax column of Nathaniel's sea captain son Leonard, it burned—a common fate with the means of heating the house and cooking meals requiring an open flame that normally went day and night. It was gratifying for me to struggle with tax records to date when the house was rebuilt on the old foundation, then to have the date confirmed by Bernice's notes. She wrote that Leonard moved his family into the new house in mid-July 1855. By the 1870s, Leonard was captaining 200-foot oceangoing barks and moved to Portland. So 142 years after the first Robert Montgomery settled in the village, the house site passed out of the Montgomery family. Fourth-generation Leonard deeded the house and surroundings to English-born James and Julia Webber in 1872.

Webbers and Barlows

The Webbers lived there until Julia's 1886 death. James continued as owner until 1898, when he deeded the house to his daughter, Mary Barlow. It passed through another three generations of Barlows: Harvey, Albert, and Bill. After four generations of Montgomerys in 142 years and five generations of Webber-Barlows in 131 years, Bill deeded it to another family, the Hambletts, in 2003. Andy Hamblett's local roots are summer ones; his Hamilton forebears came five generations ago to Murray Hill, and his Stevens forebears summered at Ocean Point for as many generations.

The preceding paragraphs are intended to put the site in context, to help people understand the old-time familial rhythms of land ownership in an old locality. Property transfers usually followed family ties until well into the 1900s. Now that pattern is growing rarer as the predominant population shifts to retirees and summer people, with the summer people handing on the houses.

Carpenter Gothic

This Montgomery house (there were any number of other Montgomery houses in the village) appears in the above circa 1890s photo. It represents the Carpenter Gothic style, which became popular in the 1840s and 1850s with features including the decorative bargeboards hanging from the roof's gable end. Some of those featues are called Stick style and you can see why from the stick nature of the decorative elements. Stick style evolved from Gothic on its way to Queen Anne. So the exterior decorative elements, the spindle work and upper porches may date to the house's 1855 post-fire construction, when those features were all the rage. Perhaps Leonard and Sarah Jane Montgomery were making a statement when they rebuilt the imposing farmhouse. It was probably as large and connected then as now since the 1864 topo map shows a long extended footprint.

Other houses in the village had or have this "gingerbread" quality, and many are characterized by sharp gables as well, which this house doesn't happen to share. I like to think the same builder created them all, gingerbread and gables sprouting all over the village. Then he went up to the road to Damariscotta Mills where they're rife, and did it all over again. Leonard's oldest brother Daniel moved to Newcastle, so I, with not an iota of proof, vote for him as the Carpenter Gothic builder. Those brothers had 15 other siblings – someone in the family had to build some houses!

A working farm

The photo was taken back when a fence had real meaning, when nearly everyone had a small subsistence farm. You had to keep the livestock and wildlife separate from your crops, so a fence kept one or the other in or out. Today people just run a length of fence or wall as a decorative accent, at most a signal to a snowplow (the plow will win). Today's symbolic fences don't enclose anything; they just imply.

You see that the horse is as close as he can get to the small vegetable garden's fence—he'd make short work of the produce inside if he could. And the dooryard too is enclosed, perhaps to preserve the flowers, cultivated berry bushes, and herbs from critters, or maybe to keep the livestock from getting too familiar. If you're sitting on the porch peeling potatoes, shucking corn, or snapping peas, you don't want cloven hooves, big or small, trip-trapping up to get the leavings. Maybe the ever well-behaved chickens were let in.

It's a great peek at another time. The house is now bare of the gingerbread trim and fences but the structure is the same, a long, extended, south-facing old farmhouse—enough remains to tell us it was once a working farm.

Address

United States