A Hawk with Socks

Rough-legged hawks are the northern-most of the hawks known as buteos. They are uncommon in Maine in winter. (Photo courtesy of dfaulder via wikimedia commons.)

Rough-legged hawks are the northern-most of the hawks known as buteos. They are uncommon in Maine in winter. (Photo courtesy of dfaulder via wikimedia commons.)

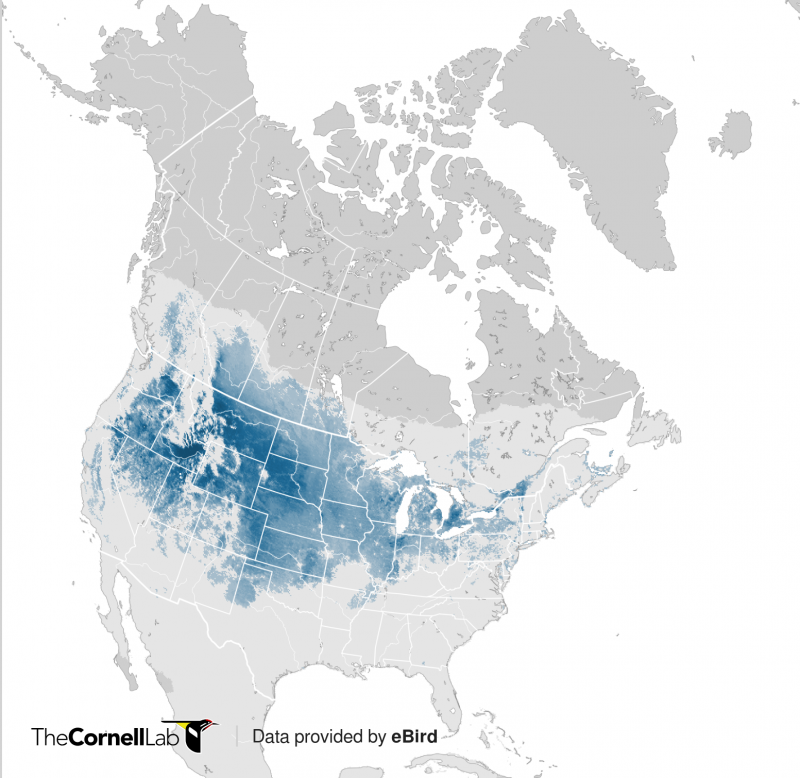

Rough-legged hawks winter across southern Canada and the northern United States, with highest numbers in the western and midwestern parts of the wintering range. (Map courtesy of eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Rough-legged hawks winter across southern Canada and the northern United States, with highest numbers in the western and midwestern parts of the wintering range. (Map courtesy of eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Of the hawks we see here in Maine in winter, only the rough-legged hawk has this striking black and white pattern. (Rough-Legged Hawk From The Crossley ID Guide Eastern Birds courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Of the hawks we see here in Maine in winter, only the rough-legged hawk has this striking black and white pattern. (Rough-Legged Hawk From The Crossley ID Guide Eastern Birds courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Rough-legged hawks are the northern-most of the hawks known as buteos. They are uncommon in Maine in winter. (Photo courtesy of dfaulder via wikimedia commons.)

Rough-legged hawks are the northern-most of the hawks known as buteos. They are uncommon in Maine in winter. (Photo courtesy of dfaulder via wikimedia commons.)

Rough-legged hawks winter across southern Canada and the northern United States, with highest numbers in the western and midwestern parts of the wintering range. (Map courtesy of eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Rough-legged hawks winter across southern Canada and the northern United States, with highest numbers in the western and midwestern parts of the wintering range. (Map courtesy of eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Of the hawks we see here in Maine in winter, only the rough-legged hawk has this striking black and white pattern. (Rough-Legged Hawk From The Crossley ID Guide Eastern Birds courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Of the hawks we see here in Maine in winter, only the rough-legged hawk has this striking black and white pattern. (Rough-Legged Hawk From The Crossley ID Guide Eastern Birds courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

We feel quite fortunate to have been viewing regularly, since late December, one or more of our favorite winter hawks—the rough-legged hawk. The bird (or birds) have become part of the scenery we enjoy as we bird our way along a large, open farmland in north Richmond. Rough-legs, as we birders like to call them, are the northernmost of the hawks known as the buteos. The most familiar of the buteos here in our area is probably the red-tailed hawk, which has the typical buteo shape of broad, long wings and a wide and relatively short tail. The other well known buteo here in Maine is the broad-winged hawk, which only occurs in summer and makes a long trek to South America for the winter.

Rough-legged hawks, on the other hand, breed well up into the Arctic, some as far as 2,500 miles to the north of Maine. Others breed as close as about 250 miles away on the north shore of the St. Lawrence, near Anticosti Island.

In winter rough-legs come south to the mid-Atlantic states in the East, to Texas in the Midwest, and to California in the West. The greatest densities in winter tend to be in the area from eastern Washington to the Dakotas and south to Wyoming. We used to see what we considered pretty good numbers in Upstate New York, when we lived in Ithaca; while these numbers are high for the eastern U.S., they are not anywhere near the overall densities farther west.

Here in Maine, we are not blessed with high numbers of rough-legged hawks. On the cold ferry boat ride out to Monhegan Island for the Christmas Bird Count in years past, it was a thrill to find a few of them hovering in the wind over the small treeless islands between Port Clyde and Monhegan. But rarely does one see more than one or two from one place anywhere in the state.

Rough-legged hawks are usually found in large open grasslands, saltmarshes or barrens—similar habitat to the tundra and open land in the far north where they nest. This winter, along with the birds we have seen regularly in north Richmond, observers have been finding them at places like the Brunswick Airport, Weskeag Marsh, and in open areas along I-295.

Although they do sit in trees to hunt like other hawks, they also have the ability to hover in one place in windy conditions, to scan the ground for the small mammals they prefer. That behavior, along with the rather flashy black or brown and white plumage, makes them quite striking, especially against our white, frozen landscape of mid-winter.

A research project has been underway for a number of years to catch rough-legs on the wintering range and put transmitters on them as a way to learn more about their migratory routes and to find out where birds from different wintering areas may be going to nest. The largest number of tagged birds has been in the western part of the wintering range where there are more of them, and we ourselves have seen only a few of the maps. From the maps we have seen, it appears as though even birds heading to places like northern Quebec and Labrador, from areas south of the Great Lakes, tend to go more-or-less straight north before moving eastward rather than flying across Maine to get there. That may or may not end up holding true as more birds wintering in the eastern U.S. and New England eventually are tagged, but it would be consistent with the fact that large numbers are not seen passing through Maine on migration.

So, have you been wondering where they get their name from? Rough-legged hawks have feathering extending down the legs—in essence, they wear socks! As you can imagine, this an excellent adaptation for staying warm in the often frigid conditions of their northern range—not unlike the reason we humans wear socks!

Jeffrey V. Wells, Ph.D., is a Fellow of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Vice President of Boreal Conservation for National Audubon. Dr. Wells is one of the nation's leading bird experts and conservation biologists and author of the “Birder’s Conservation Handbook.” His grandfather, the late John Chase, was a columnist for the Boothbay Register for many years. Allison Childs Wells, formerly of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is a senior director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, a nonprofit membership organization working statewide to protect the nature of Maine. Both are widely published natural history writers and are the authors of the popular books, “Maine’s Favorite Birds” (Tilbury House) and “Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao: A Site and Field Guide,” (Cornell University Press).