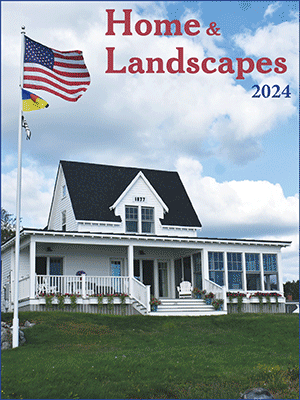

The Fullerton Homestead and Colonial Fort

Elizabeth Reed, born in the 1870s, lived in the museum building until her death in the 1950s, except when teaching in Boston and New York. Fullertons (and Reeds and Beaths) were her forebears. She wrote the following in 1944. –Barbara Rumsey

After living in Woolwich, Georgetown, and perhaps Pemaquid for a decade, William Fullerton, Sr. and family decided to purchase land in 1729 in the newly-organized Townsend (Boothbay) as laid out by Col. David Dunbar. The land purchased by Fullerton began at the very head of Boothbay Harbor at White’s Cove, named for Moses White, and extended north to Boothbay Center. On the shore his land ran south to where Marson Brothers now have a grain and oil business (now the Chowder House), then ran west just south of Hotel Fullerton (now the post office lot) to William Moore’s line (at Moore’s Rock above West Street), then north along the big meadow and up to the Center. This was perhaps the most choice of the shore lots as there were a number of springs of fresh water along by a swamp.

Fullerton’s Projects and Assets

Fullerton, with the help of his son, William Jr., immediately cut great logs from his heavy forests, dug a deep cellar, and soon reared a small log cabin over it. The cabin faced south on the western slope of a hill, and the deep spring west of the cabin he and his son dug deeper and walled up with stones in the summer of 1730. This well was filled in and covered up by Luther Barlow about 1925. While the cabin was being reared, the crops of maize, potatoes, and cabbages were growing on the hillside east of the cabin. When fall came, they were all safely stored in the new cellar.

Just how much luggage the family had is unknown but it is known that William Fullerton had a sea chest and among other necessary articles in it were certain cooking utensils, as follows. First was an iron Dutch oven having an iron cover with a turned-up rim. When the kettle was hung on the crane over the fire, hot coals were placed on this cover, the rim holding the coals in place. Thus the venison cooked quickly with heat from below and above. Another article in the sea chest was the tin baker, large enough to contain a haunch of bear meat. Children turned the crank which turned the meat thus cooking it evenly all around. The third article was a tin utensil with a shelf on the inside. On this shelf in a pan was baked the milk-raised or salt-raised bread as there was no yeast then. Five generations of Fullertons baked the milk-raised bread for the Presbyterian-Congregational Church in Boothbay Harbor. Perhaps the last article in the sea chest was the tin horn lantern. I still own all these articles, together with the sea chest. (They are now lost to us).

For the next fifteen years, the Fullerton family was busy clearing the woods away from in front of the cabin, draining the swamps, and building a little stone bridge over the brook (maybe the Stepping Stones that people used up to the 1950s). A lean-to had been built and the family had been enriched by the advent of a yoke of oxen, two cows, a pig, some fowl, and some farm tools. All these had been acquired at great expense and had strained the family purse, but they made life more livable and farm work less of a drudgery.

Indian Trouble and Stone Fort

Up to 1745, the Indians had not been very troublesome in the Townsend region, but King George’s War had begun in 1744. Now the little settlement clustered around the harbor lived in a constant dread of a massacre, hearing of the bloody work in Sheepscot, Damariscotta, and Broad Bay. They could move over to Fort Frederick at Pemaquid; they frequently went there to hear Chaplain Dennis preach. But if they did so, they feared their cattle would be killed and their cabins burned.

In self-defense, Fullerton with the aid of his stalwart son and Beath relatives built a stone garrison on the western slope of his big hill a few rods from his salt water cove. A picket fence surrounded it; also fenced was a path leading down to the flats so that they could dig clams and fish for cunners at high water. This fort stood where Frank B. Greene’s garage now stands on Oak Street (Roughly behind the Opera House and its adjoining parking lot). As a little girl in the 1880s I used to wonder what those huge loose rocks and boulders were doing lying about so oddly under the oak trees there. These rocks were later used in building up the road bed there. (Asa Tupper told me that the road area there was called “Bob DeWolfe’s Fortification” by those who knew the rocks had been part of a fortified stone house. DeWolfe was the road commissioner who built up the road and sidewalk with the rocks. Barbara Rumsey)

British Press Gangs

After the Indians had killed some of the more distant settlers, the rest of the inhabitants fled to William Fullerton’s stone house. The men organized themselves into a little military force and took turns as sentries day and night, guarding those going down to the shore for clams. As the warfare grew more violent, many fled westward to Boston where they had relatives. Suddenly a British man-of-war appeared in the harbor and press gangs seized and carried off all the young able-bodied men in the settlement, leaving only older men to guard their little fort. They had in vain appealed to the Massachusetts Bay government for help and protection such as had been granted to surrounding towns.

So the older men had to guard the little settlement. As feared, the Indians burned their cabins and killed their cattle. But when news of the peace of 1748 reached Townsend in 1749, the settlers ventured back to their lands and rebuilt their cabins.