A closer look at the ER

Of all the changes proposed at St. Andrews, the conversion of the emergency room to an urgent care center continues to raise the most public concern.

National and state trends

Emergency medicine is a relatively new medical specialty, arising out of practices developed on the battlefield during the Korean and Vietnam wars. Emergency rooms were not common in U.S. hospitals until the 1960s – and board certified emergency physicians did not exist until the 1980s.

The public quickly embraced emergency medicine and ERs since they offered a unique service. Hospital emergency rooms provided round-the-clock care to patients, regardless of their ability to pay or level of need.

Walk in and you will receive care.

The Center for Disease Control reported that there were 136.1 million visits to U.S. emergency rooms in 2009.

In addition to providing care for true emergencies, the ER’s open-door policy and 24-hour service made it a convenient solution for patients who sought care outside of regular office hours. Because they were located in hospitals, ERs also usually offered diagnostic services, such as laboratory and imaging, and provided the patient “one-stop” service not available at doctor’s offices.

National and statewide studies have indicated that many ER visits are for non-urgent purposes.

A 2007 Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP) national survey reported that at least one-third of all ER visits were avoidable and non-urgent.

But what is medical urgency? Level of urgency can be influenced by factors such as time of day, day of the week and availability of other providers. In a 2011 statement to the U.S. Senate, Center for Studying Health System Change Director, Dr. Peter Cunningham, said “most ED visits are neither clearly non-urgent nor truly emergencies.”

In rural areas, ERs may fill a healthcare gap. A 5-year national rural emergency department survey found that ERs in critical-access hospitals saw a significantly higher percentage of low severity cases than urban hospitals.

The Muskie study found that non-urgent ER users in Maine often said the long wait for a medical appointment, difficulty taking time from work, high primary care physician turnover and the ER’s efficiency were their reasons for choosing an ER for a health problem that wasn't urgent.

A 2011 Center for Disease Control survey reported that 80 percent of adults said that they had been to an ER that year because of a lack of access to other providers.

But emergency rooms are costly places to obtain care. The 2007 ACAP study estimated that “over $18 billion are wasted annually” on avoidable ER visits in the U.S. The same study estimated that in 2006 Maine’s “wasted expenditures” on avoidable emergency visits topped $100 million.

A 2006 Institute of Medicine report estimated that the cost of non-urgent care in emergency rooms was two to five times higher than the same care in a private practice setting.

National studies have shown that overall ER use in the U.S. has been rising faster than the population has been increasing. Overall, most of the increased ER use has been driven by the insured – with the uninsured visiting the ER more for primary care, Cunningham reported.

In some hospitals, non-urgent ER use can further clog already crowded emergency rooms, affecting the quality of care, the capacity to treat patients, and forcing hospitals to divert ambulances to other facilities.

St. Andrews ER data

Emergency room use at St. Andrews Hospital has not followed the larger national trend. Since 2007, Lincoln County Healthcare CEO Jim Donovan reports that ER visits have declined steadily from 4,692 visits in fiscal year 2007 to 3,751 visits in fiscal year 2011; that's a 20 percent decrease over 5 years' time.

In a letter to local residents, Lincoln County Healthcare wrote, “Because the vast majority of ED visits occur during the day and 82 percent of all ED visits do not require emergency care, the St. Andrews Emergency Department will be transformed into an Urgent Care Center.”

The urgent care center's proposed hours are from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. in summer months and from 8 a.m to 6 p.m. the rest of year.

The St. Andrews ER data summarized by their consultant company Navigant included patients scheduled to use the ER for specific therapies but who were not true ER patients, according to Donovan. The Navigant analysis showed roughly 800 daytime visits to the ER data set, which should not be considered.

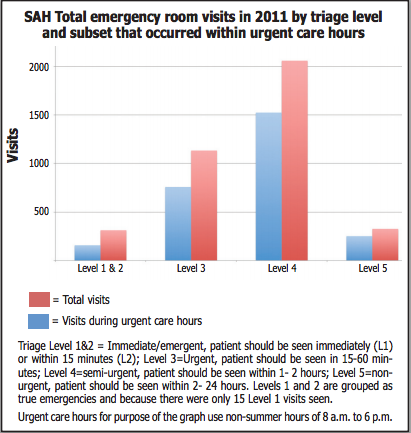

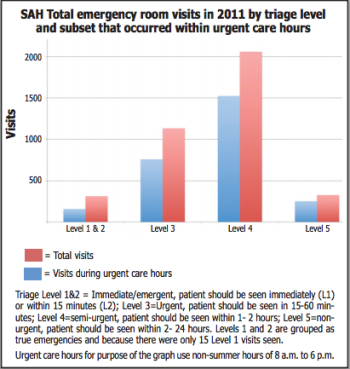

Emergency Department Director Dr. Tim Fox provided a breakdown of 2011 St. Andrews ER visits by time of day and sickness of the patient (see graph). These data, although like the Navigant analysis limited to only one year, should provide a better snapshot of ER use.

In ERs, nurses use a triage system to assess and rate a patient’s priority for care.

The sickest of the sick needing immediate care are ranked at Level 1. Level 2 is considered emergent – needs to be seen within 15 minutes of arrival. Level 3 is urgent – needs to be seen within 15 and 60 minutes. Level 4 is semi-urgent – needs to be seen within one to two hours; and Level 5 is non-urgent – needs to be seen within two to 24 hours.

The St. Andrews ER data show that true healthcare emergencies are relatively rare and do not conform to office hours.

Of the 3,834 St. Andrews ER visits reported by Fox, 313 visits (8 percent) were Level 1 or 2 emergency visits. These true emergency visits, requiring care in less then 15 minutes, averaged less than 1 a day in 2011. Of these,15 were ranked Level 1 (immediate care).

Fifty percent of Level 1 and 2 visits were between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. and 66 percent were between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m.

Patients who needed to be seen within 15 to 60 minutes (Level 3 urgent) numbered at 1,134 or roughly 30 percent of of the total ER visits in 2011. Two-thirds of these occurred between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. and 75 percent occurred between 8 a.m and 8 p.m.

The majority of patients (2387 visits or 62 percent) needed to be seen within one to 24 hours (Levels 4 and 5).

Three-quarters of these visits occurred between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. and 83 percent between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m.

Does low volume affect care?

On average St. Andrews' emergency department sees about ten patients over a 24 hour period – it is one of the least busy ERs in the state. Patients experience this low volume as a plus, because they rarely have a significant wait.

But for the hospital and emergency physicians, the low number of patients seen make it difficult to attract and maintain highly skilled staff, keep up life-saving skills and provide the level of care needed to stabilize and treat the sickest patients.

In the early days of emergency room medicine, ERs were staffed by hospital staff doctors and nurses who were not specialists in emergency medicine. They did the best they could, but a lot of people died who would not die today.

The modern ER doctor (and paramedic) is trained in resuscitation, airway management, advanced cardiac life support and other specialized procedures to handle trauma and severe illness. Emergency medicine is a proven, constantly developing discipline with a high reliance on technology and techniques.

The St. Andrews ER is presently staffed primarily by board certified emergency medicine physicians, who also work at Miles Memorial and other hospitals, and Dr. Stephen Cook, a surgeon who works only at St. Andrews ER. Emergency room nurses and emergency medical technicians are also on staff. Each 24-hour period is staffed by one doctor, one nurse and one technician.

Using emergency physicians instead of physician’s assistants or other less highly-trained doctors and nurses as some other rural hospitals do, costs the hospital – but not the patients – more.

Some have suggested the hospital return to the model of using family care practitioners or other non-specialists in St. Andrews ER, presumably as a way to reduce hospital expenses.

When asked, Dr. Fox seems genuinely surprised that someone would suggest that a lower level of emergency care is appropriate, “It’s been proven over and over again that patients do better when seen by emergency doctors,” Fox said.

Fox said that in the old days it might take an hour for a doctor to arrive at the hospital but now the ER is held to strict time response constraints and standards.

“From the door to the EKG used to be two hours in those days. Before Lincoln County Healthcare was formed, it was ten minutes in this hospital. Now, it’s door to EKG in three minutes. The standard of care and time to treatment get elevated every year,” Fox said.

Rural hospitals find it difficult to attract emergency physicians and other specialists because of the low volume of patients. Fox said during winter months at St. Andrews ER, it’s not unusual to see only one or two patients in a 24-hour shift.

“It’s one of the questions (prospective doctors) always ask. Their main concern is they are not going to see enough volume and their skills will degrade over time,” Fox said.

Jack Fulmer, a retired Florida physician and emergency room doctor who now lives part of the year in East Boothbay, has over 40 years experience in private practice, as well as in rural and large (Mayo Hospital in Jacksonville) hospitals. Fulmer scoffed at the idea that an ER doctor would want to spend time catching up on reading, as has been suggested.

“You gain your skills by doing. You become very, very good at what you do because you’ve seen it all. You can write the book. If you are sitting around staring at four walls, you can become incompetent in a hurry,” Fulmer said.

Lincoln Medical Partners Director Dr. Mark Fourre said it is only because of the association with Miles Memorial Hospital, which has three times the patient volume, that the emergency physicians currently working at St. Andrews are willing do so.

Fourre said the resources available at St. Andrews, particularly at night, can make doctors “uncomfortable” when faced with the sickest of the sick.

“At St. Andrews, we don’t have surgeons that can back us up, pediatricians, respiratory therapists, X-ray, and laboratory. If you get a really sick patient that shows up and it’s just you and one nurse at night, that’s not the right place to be.

“It’s not that it’s not a good nurse or not a good doctor or a well-run ED, it’s just so small that they should probably be in a different place,” Fourre said.

Can Miles handle the extra patients?

Miles Hospital sees three times the ER patients that St. Andrews does (12,197 ER visits in 2011) and has seen only a small decline (four percent) in ER use over the last 5 years.

Currently, Miles is staffed by one emergency physician for 24 hours, a second emergency physician who overlaps during peak hours (bringing the total for peak hours to two doctors), one intermediate level emergency room technician or paramedic who provides 21 hours each day, and emergency nurses, whose numbers range during the day from one to four.

That staffing level may change to adapt to more patients and the shift to electronic medical records, Fox said.

Miles has the ability to provide a higher level of care than St. Andrews. While St. Andrews transfers its most serious ER patients to other hospitals, and has for years, Miles admits most.

“We have the ability here to admit critically ill patients, overdoses, patients on ventilators. Our intensive care unit is connected to MaineMed so we have the ability to monitor cardiac patients. We admit pediatric patients and OB patients. The only ones we don’t keep are severe trauma and neurological emergencies,” Fox said.

Fox said he estimated the increased load at Miles ER with the closing of St. Andrews ER. In summer, Fox expects there could be an extra one to six ambulances a day – a maximum of six extra patients.

“But ambulance patients are usually sicker overall so there will be some impact. We are looking at ways to increase efficiency,” Fox said.

Lincoln County Healthcare is expecting less urgent cases to use its urgent care, but because of the limited hours some are likely to travel to Miles and other hospitals to seek emergency care.

Shortly after the St. Andrews changes were announced, Miles had to divert ambulances for about two hours because of crowding and a critical patient awaiting LifeFlight, Hospital Operations Vice President Cindy Leavitt reported.

Hospital ER diversions are not unusual, particularly for high volume ERs. Miles reported three diversions in the past year, all lasting about two hours each. Walk-in patients are not refused care during a diversion, Leavitt said.

The result of closing St. Andrews ER on Miles ER will not be known until the change occurs.

The real worry

Ultimately, people are concerned that the additional travel time in ambulances or private cars will be the difference between life and death.

Fox said he reviewed cases of the sickest ER patients in the last year and concluded that all could have been stabilized by paramedics. “If the condition is not something that can be (stabilized) in an ambulance, it is usually difficult to stabilize anywhere,” Fox said.

Ambulance travel times of 20 minutes or more are common throughout the state of Maine and would be considered short in some parts of the country.

But for local residents, who have grown up with a hospital on the peninsula, it has been hard to accept assurances that emergency response will be as good as it currently is.

Shift from emergency to primary care

The Muskie and ACAP studies found that from a healthcare perspective the availability of a walk-in clinic or same day appointments had the biggest influence on non-urgent ER use. Cunningham suggested shifting non-urgent problems to primary care providers could improve the quality of care and increase patient satisfaction overall.

It is precisely this shift that Lincoln County Healthcare is hoping to make happen through the creation of the urgent care center and other changes at the Family Care Center.

In a discussion with town task force members, Dr. Fourre said, “We really are keying in on the emergency part but if you look at the health of the population, that’s the wrong place to be spending your time and money. We should be focusing on primary care, that’s the most important piece for the community.

“And getting to what people are concerned about – building that interface between paramedics and physicians and making sure (the ambulance service) have the tools and training they need.”

For more on changes at St. Andrews, read the rest of our series:

Part III, Hospital decisions explained

Part IV, Hospital transition begins

Part V, Ambulance service plans for ER closing

For the story told through community response, visit our Storify

Event Date

Address

United States