Reflections on Rachel

After "Silent Spring" came out in 1962, Rachel Carson and her grandnephew started keeping a scrapbook.

They filled it with the many political cartoons being printed about Carson. Some were supportive; others mocked her environmental concerns. One portrayed her as the "priestess" of nature.

The scrapbook was a way to find humor in the massive stir "Silent Spring" was causing. Carson was already well-known for her earlier books, but "Silent Spring" took that fame, and the national conversation about the environment, to a new level. The book explored pesticides' impact on species they were not meant to harm. It led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and a ban on the pesticide known as DDT.

Those close to her worried about the backlash that would descend on Carson, said Stanley Freeman Jr., whose parents were some of Carson's closest friends.

"But she went ahead anyway, because she had this calling that somebody had to tell this story that we're being poisoned," Freeman Jr. said. "She was a very private, gentle lady and she stood up to forces much bigger than any of us."

Freeman Jr.'s parents met Carson after his mother, Dorothy Freeman, read in the Boothbay Register that the author was building a cottage in Southport. She wrote Carson a letter that "welcomed her to the shore of Southport Island. She did this without knowing her at all and never expected a response," Freeman Jr. said.

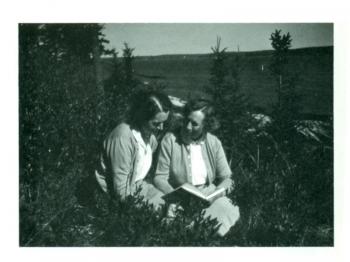

But Carson did respond, and in the summer of 1953 "my father and mother had tea with Rachel Carson," he said. "From that point on, Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman became very close friends."

Carson dedicated one of her books, "The Edge of the Sea," to Dorothy and Stanley Freeman Sr.

In Southport and at the site she chose for the cottage in particular, Carson "was able to find a kind of ideal place," with tidal areas to explore near the mouth of the Sheepscot River, her grandnephew and adopted son Roger Christie said. "She loved it."

Carson taught Christie "a general respect for the natural world, and a sense of the connections between things that aren't obviously apparent," he said.

The Freemans were "the best part" of his and Carson's summers, he said. "We saw them all the time."

Freeman Jr.'s daughter Martha Freeman was a playmate of Christie's on the island. She remembers being with Carson when the writer would borrow tide pool creatures to view them under a microscope. "She always took them back to their little homes," Martha Freeman said.

"I just remember this quiet, teaching kind of presence," she said. "I was so impressed with her fortitude and her ethics and the deep love she felt for nature, and the responsibility she felt to tell the world what she knew to be the truth about the biological relationships between people and the environment. So, she just impressed the heck out of me."

On one especially dark summer night, Martha Freeman, about 5 then, watched Carson writing in the air with a sparkler.

"And I just thought she was the most magical thing I'd ever seen," she said.

Martha Freeman grew up to be a lawyer and now heads the University of Southern Maine's human resources department. In the mid-1990s, she compiled many of the letters her grandmother and Carson wrote each other into the book "Always, Rachel."

Carson "was a quiet person. She was not a rabble-rousing person at all," Martha Freeman said. "But, as she said in her letters, she couldn't live without knowing she had tried to save people from themselves. There was so much pushback on her, for just trying to tell the truth."

The care Carson took to write "Silent Spring" helped it withstand the chemical industry's attempts to discredit it. Christie still recalls Carson's hard work on the footnotes. "She agonized over that for months," he said.

Christie is a recording engineer living in Harvard, Mass. He still gets back to the Southport cottage when it isn't being rented. It's his now, and his time there brings back good memories of dirt roads and penny candy, the Freemans and the great aunt who adopted him. She was a stronger person than most people realize, he said.

Freeman Jr. witnessed that strength the last time he saw Carson. It was January 1964, after his father died. He remembers helping Carson onto her plane after the funeral. Although she used a wheelchair and was increasingly ill from breast cancer, "she was so determined to salute my father and my mother by being there that she made that difficult trip," he said.

Carson died that April.

Dorothy Freeman would later release Carson's ashes in Southport, near the Newagen Inn (now the Newagen Seaside Inn). The two women spent many hours sitting on the rocks there, "watching life go by, with the sky and the sea between them," Freeman Jr. said.