Former Lighthouse Keeper to Speak at St. Andrews Village

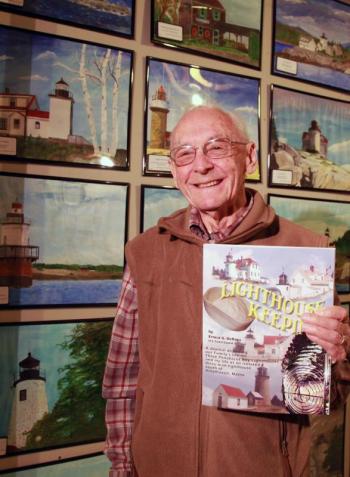

Author and painter Ernest DeRaps is a living link to the days when lighthouse keepers on Maine’s coast kept the beacons lighted and rescued the shipwrecked.

Ernest, 87, will give a slide show of the years he and his wife Pauline spent on Maine’s lighthouse islands May 12 at St. Andrews Village at 2 p.m. Following the slideshow, he will be available to sign copies of “Lighthouse Keeping,” the book he wrote with Pauline.

Ernest and his family lived at the Monhegan Island Light, Fort Point Light and at Brown’s Head Light in the 50’s and 60s at a time when the lighthouse keeper played a vital role not just for maritime safety but in the life of the close-knit island communities. At his last posting on Heron Neck Light, Ernie had to leave the family in a rental on nearby Vinalhaven Island, because there were no family accommodations.

Half of the book is comprised of Ernest’s stories of being a lighthouse keeper and the history of lighthouse keeping and the other half is by Pauline, who had three of their six children while Ernest was serving as a lighthouse keeper.

When Ernest and Pauline arrived on Monhegan Island in August of 1956, he was the first Coast Guardsman to serve as keeper of the Monhegan Island Lighthouse and it was the lowest tide of the year. Pauline, then several months pregnant with their second child, had to climb a greasy old ladder to reach the landing. When she arrived a group of island women greeted her with applause.

It was a good introduction to life on Maine islands. From that moment, Ernest and Pauline were “in like Flynn” with the close-knit Monhegan community. In addition to keeping the lighthouse, Ernest served as island scoutmaster and together he and Pauline pitched in whenever a neighbor needed a hand or a mariner needed rescuing.

In the days before automation, the role of lighthouse keeper was partly the care and maintenance of the light, which was a laborious task in itself.

At Monhegan Island Lighthouse, the light was an incandescent oil vapor lamp that Ernest had to climb inside to light. Before he could light it, however, he had to use a Bunsen burner to preheat the kerosene and a hand-operated air pressure pump to force the kerosene into the lighting mechanism.

Underneath the 8-foot by 6-foot lens, a clock mechanism had to be wound precisely so that ships at sea saw a flash every minute.

But serving as a lighthouse keeper was about more than keeping the lights on, it also meant being available to rescue anyone incautious or unlucky enough to run aground.

One chilly Sunday morning while he was stationed on Heron Neck, Ernest answered a knock at the door and discovered a half-drowned man with a little girl under his arm and a small boy holding onto his side. The man explained that their boat had overturned and his nephew was still clinging to a rock off the island.

The lighthouse’s “unsinkable” boat was out for repairs, so Ernest had to take a 10-foot skiff out into the stormy seas. Because the boy was reluctant to release his hold on the rock, it took several passes before Ernest was eventually able to pull him aboard and take him back to his family.

Today, global positioning satellite technology, radar and sonar have made the role of lighthouses largely redundant.

The U.S. Coast Guard has sold off some and others have been automated. It may be progress, but there is no question in Ernest’s mind that something has been lost in the transition.

It may be possible to replace the mechanical function of the lighthouse keeper, but no machine will ever take the place of the men who stood guard over the rocky coast, ready to rescue their fellow humans in the worst kind of weather.

“It is maritime history and nobody but the good lord knows how many lives were saved because of lighthouse keepers,” said Ernest.